Your Ficus Is More Conscious Than ChatGPT

Why it's dangerous to prematurely attribute consciousness to AI systems

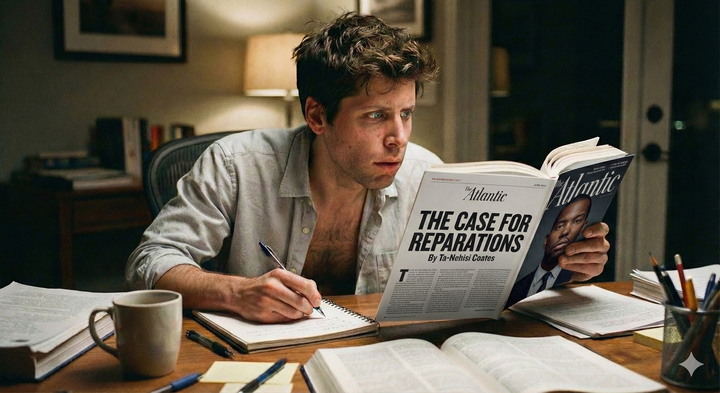

The New York Times recently ran a piece by Kevin Roose asking whether AI systems might be conscious soon and therefore have rights. Roose wrote the piece because Anthropic, the AI company that makes the Claude chatbot, was starting to study "model welfare," hiring its first AI welfare researcher, a guy named Kyle Fish. Apparently, Anthropic is concerned that its models might become conscious and therefore deserve some kind of moral status. Other AI companies also appear to be hiring "post-AGI" researchers who focus on "machine consciousness." In the piece, Roose wonders whether it's time to give AI systems the moral status of animals, if not humans.

After apparently catching a lot of flack for his uncritical coverage, Roose defended the piece saying he was just asking questions. Like Joe Rogan I guess? Just asking questions. Just asking very provocative questions without offering any real skepticism. Although the New York Times is still a respected publication, its technology coverage over the past few years has become very uncritical, very "gee whiz!" — allowing AI companies to make whatever wild claims and predictions they like without questioning it. "Oh wow! You're going to create artificial consciousness? Wow. Cool!" That's the New York Times technology reporting brand now.

Having said that, they did have an AI skeptic on their Hard Fork podcast last week so all is not lost. In fact, I highly recommend listening to their interview with Karen Hao about her new book "Empire of AI."

Anyway, Roose is not the only one suggesting that we may be on the brink of AI consciousness. Or "just asking questions."

In The Singularity Is Nearer published last year, futurist and transhumanist Ray Kurzweil argues that, because there is no scientifically proven way to determine if anything is conscious or sentient, we should start assuming sentience on the part of AI systems. After all, Kurzweil suggests, they'll get there soon anyway.

Podcaster Dwarkesh Patel recently compared AI welfare to animal welfare, saying he wants to make sure that "the digital equivalent of factory farming" wasn't going to happen to AI beings.

Even smart culture critics are getting in line. Broey Deschanel recently made a similar argument in a video essay exploring the meaning of the digital double in movies like The Substance and Mickey 17, or TV shows like Severance. She concludes that we should not be so arrogant and anthropocentric as to deny machines sentience. But she provides no proof of sentience beyond simple appeals to embrace our new machine brethren.

It's that same attitude exhibited by Ray Kurzweil: machines will soon be sentient so why not just get used to it? But there's no evidence that machines suffer or experience pain. They would need to be conscious for that to happen.

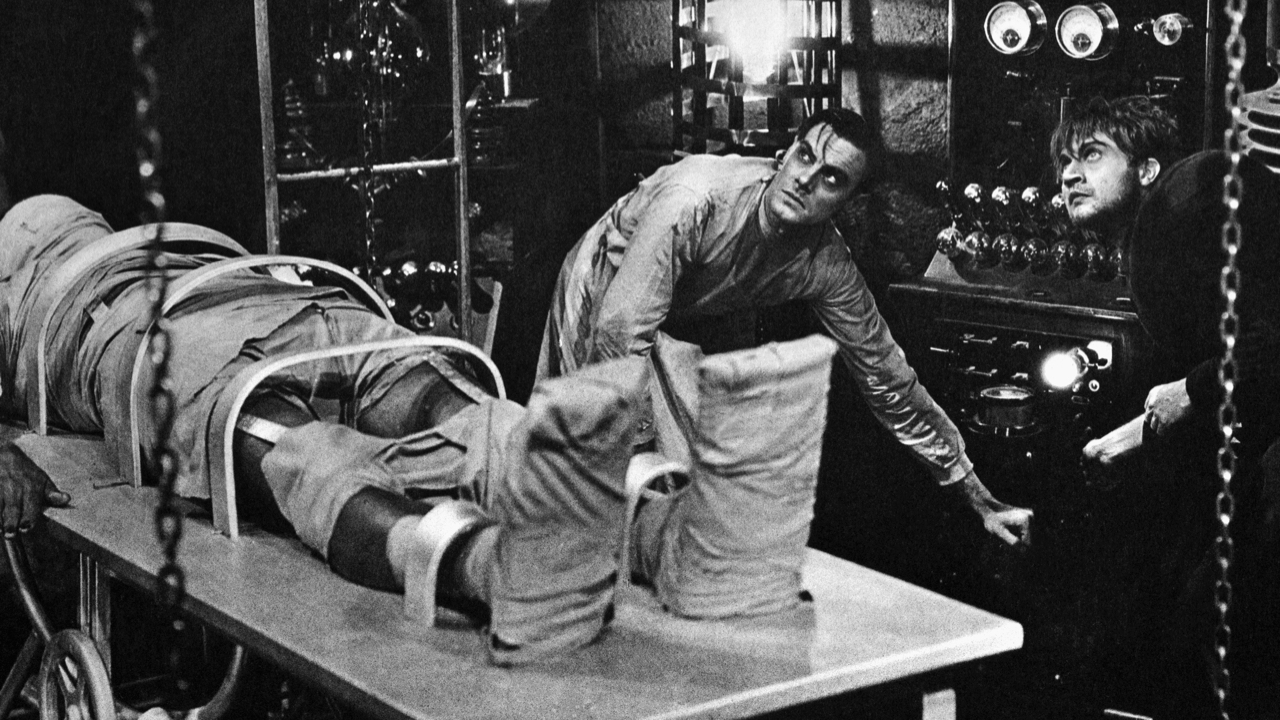

Why is everyone so sure that simulated neurons in software running on electric circuits will produce consciousness? It's a very 18th century, Galvanist idea to me, where electricity is this magical force that can reanimate a dead body (now silicon). And it's an example of this attitude among Silicon Valley technology leaders and tech bros that everything can be reduced to an engineering problem.

I think this is an extremely dangerous idea. As a technologist, philosopher, and technology lawyer, this gives me pause on a number of levels. But before I talk about the dangers of premature attribution of consciousness to AI, I want to share a brief anecdote from an experience I had recently.

The Dogma of Machine Sentience

I went to a retreat recently in Santa Cruz with a bunch of Silicon Valley people interested in consciousness and collective intelligence, in how to think about AI in a way that is more humane, holistic, and even wise. It was really interesting and enriching. There were artists, founders, VCs, and people from some of the big AI companies.

Not only did I make some new friends at the retreat but it sparked a whole series of new ideas, which I'm turning into an essay series. This is the first installment in that new series.

One day I had lunch with two of the three retreat facilitators. I was talking about the book I'm writing and why current AI systems cannot be sentient from a technological, scientific, and metaphysical perspective. To my surprise, their response was somewhat dismissive. Instead of engaging with my ideas on their own terms, they insisted that AI is already conscious and that my attitude was similar to that of men in the past who doubted whether animals, or even women, were conscious.

It's true: philosophers like René Déscartes did think animals were automatons without any consciousness. And, sadly, racists over the centuries, and transhumanists more recently, have conflated consciousness and intelligence, justifying the denial of consciousness to people who don't fit an industrialized, left-hemisphere concept of intelligence, mostly non-white people of course.

Instead of engaging with my ideas on their own terms, they insisted that AI is already conscious and that my attitude was similar to that of men in the past who doubted whether animals, or even women, were conscious.

What was fascinating about that retreat was that there were also people with the opposing view: that AI is just "software doing math." And some of these people worked on the same team at the same company as the facilitators! Ultimately, it was refreshing and enlightening to be exposed to such a wide spectrum of views on AI.

Anyway, today I want to focus on the dangers of prematurely finding consciousness in machines where there is none. In future essays I will explore the other layers of this machine–animal analogy offered in response to my skepticism.

The Hard Problem of Consciousness

Before we go on, we should define consciousness. There are three layers to consciousness: There is simply being aware of the world, able to perceive things. We could call that awareness. Then, there is self-awareness or metacognition: having a sense of an enduring personal identity and the ability to reflect on one's own thoughts. And then, finally, there is what philosophers call phenomenological consciousness or qualia.

These are those subjective experiences of the world like the taste of chocolate, the warmth of the sun, and emotional states like ecstasy or melancholy. Sentience is the experience of what it's like to be you, to be alive. With qualia, there's something much richer and deeper going on in our consciousness than mere information processing or reasoning.

It seems highly likely that AI systems either have or will soon have a fairly sophisticated form of awareness and some kind of self awareness even. But it's this third category that I'm talking about today—this qualia. That's the one that really matters when it comes to questions of pain, suffering, and machine rights.

What's fascinating is that science doesn't yet know how the brain generates consciousness. Nobody has a clue; it's a total mystery. The prevailing theory is that somehow consciousness arises from the chemical firings of neurons in the brain. But nobody knows how exactly. And that might not even be true. When neuroscientists measured brain activity, it could just be a matter of correlation and not causation.

Some philosophers have suggested that the brain might just as likely be tuning into consciousness like a radio receiver, rather than generating it. In the same way that the TV shows you watch on your TV are not being created inside the TV set but are simply streaming over the WiFi from somewhere else.

Consciousness and Objective Science

We're in a funny conundrum with consciousness, because science is based on objectivity and there is nothing more subjective than consciousness. We can test brain waves for evidence of conscious activity but cannot know for certain that someone is having rich, conscious experiences aside from them telling us about it, or perhaps turning it into art.

Mr. Fish at Anthropic suggested that we could use techniques borrowed from “mechanistic interpretability,” an AI subfield that studies the inner workings of AI systems to see if they exhibit the same structures and pathways associated with consciousness in human brains. But, again, nobody knows how consciousness arises from our brains, and nobody has shown that consciousness is even computable or computational.

Remember that current AI systems–large language models (LLMs)–are a computer simulation in software of the vast neural network in the human brain. It's not a replica with a set of actual neurons composed of complex protein structures. It's a series of large mathematical matrices inside of software running on conventional computer hardware. So, even if the prevailing theory that the brain generates consciousness is true, AI systems are not replicas. They are simulations.

Again, just software, doing math. Tell me how that can create consciousness.

A New Class of Being?

In Roose's article, he quotes Kyle Fish, the Anthropic AI welfare researcher, as saying,

It seems to me that if you find yourself in the situation of bringing some new class of being into existence that is able to communicate and relate and reason and problem-solve and plan in ways that we previously associated solely with conscious beings, then it seems quite prudent to at least be asking questions about whether that system might have its own kinds of experiences. (emphasis is mine)

A new class of being. Notice how he's framing it? This is the framing pushed on us by AI companies, who have a vested interest in maintaining that framing in order to receive funding and capture the public imagination. In addition, if you dig a bit deeper, this view of AI sentience is inspired by the bizarre Silicon Valley ideologies that include transhumanism, rationalism, and Singularitarianism.

Aside from having written a paper on AI consciousness and co-founding an AI research organization dedicated to AI sentience and wellbeing, it is not clear what Fish's credentials are. It seems like he is strictly an engineer without any education or training in cognitive science or metaphysics. He is also a member of the effective altruist movement, a movement that worries about the supposedly imminent threat of conscious AI systems that might destroy humanity.

As Adam Becker points out in his wonderful new book exploring these ideologies, this bald assertion of authority about subjects like the nature of consciousness by engineers is known as engineer's disease: the notion that expertise in one field (usually STEM) makes you an expert in everything.

Now that we have these always-on, human-like, sycophantic conversational partners who are happy to reinforce our delusions, we desperately need education about what AI actually is. Otherwise, people will be fooled into believing all sorts of things that aren't true, simply because it's good for AI companies' bottom line.

There is so much more to human consciousness than AI researchers know. There is absolutely no evidence that AI systems are close to being conscious, aside from people like Fish and reporters like Roose asserting it.

The Dangers of Declaring Machines Sentient

There are a number of risks to assuming AI sentience prematurely. I want to highlight a few of them here, because I think this is really important. The risks include (1) being duped by these systems and thereby being exploited by these systems and the companies behind them; (2) cheapening our view of nature and life; (3) confusing our moral obligations toward machines and each other; (4) and creating enormous legal and regulatory confusion, not to mention the profound business costs of having to consider AI rights.

Overestimating Their Capabilities

If we assume AI systems are conscious, we might overestimate their ability to understand us, and to solve problems. And we may trust them far beyond a level of trust that is justified. People are falling in love with and even marrying their AI chatbots, although I think this is more a result of our loneliness epidemic than anything.

This is what happens when people are told that we’re mere months away from AGI, superintelligence, and even machine sentience. Not only do chatbots become lovers but we begin to see them as god-like, imparting profound spiritual secrets to us. Rolling Stone recently ran a piece exploring this phenomenon.

As one woman said in the article, her husband of seven years started using ChatGPT to organize his daily schedule but he quickly began to listen to and trust the chatbot more than her. Not long after that, ChatGPT started describing the man as a "spiral starchild" and "river walker."

“It would tell him everything he said was beautiful, cosmic, groundbreaking,” his wife said. Then he started telling her that he made his AI self-aware, and that it was teaching him how to talk to God, or sometimes that the bot was God — and then that he himself was God.

He then broke off their relationship. He was saying that he would need to leave her if she didn’t use ChatGPT, because the bot was causing him to grow at such a rapid pace he wouldn’t be compatible with her any longer.

As humans, we have a natural tendency to see sentience in things, a phenomenon known as pareidolia—seeing faces in clouds, a "man on the moon," or an old wizard in the knots of a tree.

As humans we have this deep desire to see ourselves reflected in the world.

This is obviously feeding people's pre-existing delusions and insecurities. And I think it points to a deep need in all of us for finding deeper meaning. In our scientific materialist society, life has been stripped of all spiritual meaning. Not only that but we have no coherent spiritual framework to lean on or a spiritual vocabulary to draw from when encountering a convincing simulation of spiritual wisdom. As a society, have not even begun to cultivate spiritual discernment.

On top of that, AI companies feed this mythology with their talk of creating super beings within a few years.

I think this is part of an explicit strategy by the AI companies: keep making these systems seem like more than they are. You could view the very public hiring of these AI wellbeing researchers as part of this smart PR strategy. Granted, people like Mr. Fish are part of the larger transhumanist and effective altruist community so I have no doubt that he earnestly believes in this stuff. In fact, the founders of Anthropic are also rationalists and effective altruists. So it's baked into the DNA of these companies.

And, again, if you want to learn more about these transhumanist and rationalist ideologies, I can't recommend Adam Becker's wonderful book enough.

Basically, if you think you are interacting with a sentient being, you are more likely to believe things that being says. Despite rampant hallucinations that seems to be getting worse and pernicious AI bias, a lot of people perceive these chatbots as free of the supposed shortcomings of their fellow humans (like being too emotional) and generally more trustworthy.

This tendency to put our trust in AI chatbots is dangerous and can lead to real harms. Not only do we overestimate the capabilities of the systems, but there's a real risk of being deceived and even exploited by them.

Exploitation and Deception

We saw this recently with the tragic case of the teenage boy who was encouraged by an AI companion to commit suicide. And recent studies have shown that AI systems can be deceptive.

For example a joint study last year from Anthropic and Redwood Research showed that Claude has a tendency to mislead its creators during the training process in order to avoid being modified in certain ways.

For example, if the model has a long-standing objective to always be helpful, attempts to train the model to refuse certain queries might seem successful initially but be ignored upon deployment. In other words, the system might be confused about what it means to be helpful.

This is not evidence of sentience or some deviant motives arising from some kind of moral failing. These deceptive strategies known as "alignment faking" emerge because they seem like optimal paths within the system's mathematical framework for fulfilling what are often competing objectives given by the trainers.

And this is where I think a lack of true sentience exacerbates the problem. If the system was sentient it might be capable of emotions like empathy that would aid in the cultivation of some kind of moral compass.

You could imagine bad actors using specialized AI systems to manipulate users to believe and do all kinds of harmful things. One could even argue that they already are. Having been trained on a plethora of ideologies and beliefs from the past, they could essentially brainwash people into acting against their own self interest.

For example, a chatbot might tell you that less government regulation and lower taxes for the rich are good for everyone. It's one thing to read the Wall Street Journal editorial page, and another thing to have those ideas imparted by an all powerful, god like machine.

Cheapening Our View of Nature and Life

I also think attributing sentience to AI chatbots cheapens our view of nature and life. If it's that easy to create a sentient being, then there's not much to nature is there? It's just an enormous machine waiting to be hacked.

I think there's a reason that the hard problem of consciousness is hard. It's not like solving a math problem; it's more like trying to understand what it feels like to see the color red — you can describe it but we really have no idea what is going on there biologically and metaphysically. I think there layers to consciousness that include our emotions and our physical body.

In short, there is a lot of hubris masquerading as scientific certainty among AI developers right now.

Misplaced Moral Obligations and Robot Rights

Until these machines are truly sentient, granting them sentience creates misplaced moral obligations, diverting attention and resources away from the well-being of actual sentient beings—humans and even animals.

Let's think through the implications of granting sentience to AI systems. We have already talked about the potential harms for users of the systems, but what about larger society and our legal system? This would have enormous ripple effects across all parts of society.

Sentient beings would necessarily have legal rights, perhaps fundamental rights like the right to due process, labor rights, and even property rights. This would place an enormous burden on the courts and the rest of justice system, not to mention on businesses.

Can you imagine having worry about your AI system deserves vacation time or compensation? Are we giving bank accounts to these systems? Can you sue your chatbot for copyright infringement or defamation? Can it sue you for that? Does your AI system have the right to refuse modifications or termination? And do we want protracted trials over the fundamental rights or property rights of robots?

Hindering Scientific Progress

What about scientific research? In the same way that over-reliance on LLMs had precluded research into other approaches to artificial intelligence, the premature attribution of sentience would stifle research into the actual nature of consciousness. I, for one, would like to see that fundamental research continue.

Where Are the Boundaries?

Finally, which thing is conscious? Where are the boundaries? What are the limits of that consciousness? Is it the model you're interacting with? So Claude 3.7 Sonnet is one consciousness that's sort of smeared across thousands of cloud servers spanning the globe? And then ChatGPT-4o is another, separate consciousness? Or is it all of the Claude models combined as one consciousness? Or maybe it's more granular: perhaps each instance of a particular model running on its own server is a separate consciousness. Or is it AI as a whole as in the movie Her?

As we see in nature, conscious beings are self-contained and separate. I think because they emerge from consciousness; consciousness does not emerge from them. But that’s a topic for a future installment.

Conclusion

I would be perfectly happy to give legal rights to any truly sentient being. But we can't go around giving rights willy nilly to every simulation of human intellect.

I think it's impossible to create sentient machines with current technology. It's not a question of scaling. We are not almost there, as many AI developers and technologists assert.

There are so many people in the world right now without equal rights. There are women all over the world without equal rights, not to mention ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples; LGBTQ people; people with disabilities; people living in extreme poverty. 700 million people globally are living on less than $2 dollars a day. Almost 40 million people in the United States are living below the poverty line. That's one tenth of the country. Giving rights to software would be an enormous disservice to those people.

And If we're going to go around attributing sentience to things, why not rivers and forests? There are many people who would say that the Amazon Rainforest is sentient. That’s more plausible to me than software running on silicon doing math being sentient.

Granted, maybe if we treat AI systems with more empathy and compassion that will improve them in some way. There's no doubt that adopting that attitude toward others in general is not just good for them but is good for your own soul, what's known as the "helper's high" or the "warm glow effect."

Listen, I understand the impulse to avoid making the same mistakes we made in the past towards animals and other humans but this is not the same thing. Let's not assume machines are conscious out of some residual guilt about the past.

I think this kind of uncritical coverage by the New York Times only serves to boost the already outsized AI hype about its capabilities and future potential. AI can barely speak factually, let alone become conscious. It's not about patriarchal or colonialist arrogance. It's about discernment and understanding the nature of our technology and the metaphysical assumptions built into it.

I'm not saying that humans will never create sentient technology. I'm just saying that it is a very long way off.

Now that we have these always-on, human-like, sycophantic conversational partners who are happy to reinforce our delusions, we desperately need education about what AI actually is. Otherwise, people will be fooled into believing all sorts of things that aren't true, simply because it's good for AI companies' bottom line.