The Wisdom of Death, Part 1

Bryan Johnson's immortality project, the medicalization of death, and society's need for more "mortal intelligence"

Today, I am offering some thoughts on the “Don’t Die” guy, part of a sample chapter from my forthcoming book on being human in the so-called “Intelligence Age,” and some musings about society’s strange relationship to death and dying. Next time I will show how transhumanist immortality projects are a manifestation of our estranged relationship with death, and how we might develop a healthier relationship to death.

I wrote most of this before the wildfires hit Los Angeles. But I am sending it from Los Angeles during the wildfires that have consumed over 63 square miles of land, neighborhoods, loved ones, memories, hopes, and dreams. There is something deeply poignant about writing about death in the midst of a fiery devastation, a time when nature is speaking very loudly about our disconnection from her. I am dedicating this post to David Lynch and everyone who lost loved ones or homes in the wildfires.

Consciousness lives on. The body is like a car, and the driver is the spirit, the bit of consciousness, the atom, the soul, you could say. And so the car gets old and rusted and falls apart and the driver gets out and continues on. — David Lynch

Bryan Johnson’s Immortality Project

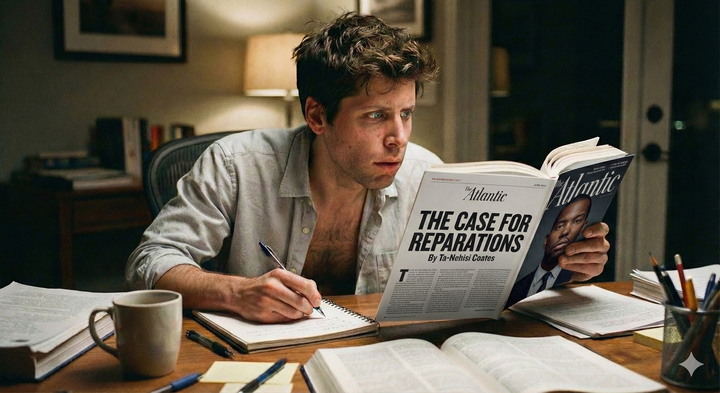

I recently watched the new documentary on Netflix about Bryan Johnson, the 47-year-old tech-bro centimillionaire in Los Angeles who spends $2 million per year trying to reverse his aging process and never die. Johnson is also hosting a series of "Don't Die" summits; the first was here in Los Angeles on January 18, and two more are planned: one in New York City in February and another in Miami in March.

I have been aware of Johnson for a while as a result of researching the chapter in my book about transhumanism, death and dying. He is a fascinating figure.

For the past few years, Johnson has been focused almost exclusively on engineering his body to age more slowly, if not in reverse. He has developed a regimen he calls Blueprint, which includes an austere, vegan diet, human growth hormone, blood plasma infusions (including from his own son), and—most risky—gene therapy. Gene therapy can result in infection, organ damage, liver damage, and even cancer.

Johnson spends over $2 million per year on this anti-aging project, and consults a team of 30 experts. He takes 111 pills daily and is constantly testing and monitoring his vitals. Johnson wears a baseball cap that shoots red light into his scalp to promote hair growth, and sleeps with a device attached to his penis to monitor nighttime erections (a higher number means a lower biological age).

Johnson's Blueprint project struck me as a desperate attempt at gaining absolute control over his life, to the exclusion of fun, spontaneity, or deep human connection. In the Netflix doc, although he acknowledges the need for social connection and community, citing "the science on it," he "has no plan" to address that, although perhaps his “Don’t Die” summits are a way of addressing his isolation.

In short, Johnson seems lost, exhibiting an overabundance of self loathing, which manifests as an obsession with not aging or dying. As I watched the documentary, I kept wondering whether he has had any therapy or done any kind of work on his emotional self. Nobody asked.

Because he spends most of his waking hours working on his body in various ways and mostly avoids sunlight, Johnson is a great example of the Joan Halifax sentiment that "when you avoid death you also avoid life."1

Johnson’s Desperate Search for Meaning

Bryan is a former Mormon and it's pretty clear watching the documentary that he replaced the spiritual meaning of his former religion with an obsession with his body, and with not dying. It is a great example of how a physicalist worldview devoid of deeper spiritual meaning results in a doubling down on the material, and attempts to become immortal through technoscience. In our postmodern world, when we cast about for meaning, technology is the first place we look.

Of course, from a spiritual, Yog-Vedantic, or philosophically idealist perspective, we are already immortal, part of Cosmic Consciousness, the Tao, Mind at Large, or Wakan Tanka. I will have more to say about all that in an upcoming series.

Body vs. Mind

Another fascinating aspect to Bryan's story is his repeated denigration of his mind. He claims to have replaced what he sees as an unreliable and weak mind with listening solely to his body and these algorithmic health regimens he has devised with the input of over 30 experts. It is a perverse kind of embodiment, where the mind is only seen as a problem, instead of something to be refined and evolved through mindfulness or wisdom practices.

Narcissistic Savior Complex

Like many tech millionaires and billionaires, he channels an impulse to save humanity through a narcissistic lens. Although he is sharing Blueprint with those willing to pay, as some of the doctors and scientists in the documentary point out, he could be using the millions he's pouring into his own health for rigorous clinical trials that would actually lead to new, replicable advancements. Because he is not doing that, any alleged age reversal or other health benefits he experiences are likely unique to him. Johnson is also combining myriad approaches all at once, making it even more difficult to tease out what is beneficial and what is not. For example, he takes hundreds of pills every day without understanding their interactions. And there is no control group for any of it.

I do admire the way Johnson is attempting to shift the emphasis in healthcare from addressing symptoms to preventative health. We could definitely use more of that in our healthcare system.

In short, Johnson is a great example of our unhealthy relationship to death as a society, and the transhumanist impulse to engineer our way out of aging and death. In the Netflix documentary, he claims that he is not afraid of death, that he loves life. But it is clear to me that he is terrified of dying, terrified of the void that awaits physicalist technologists who have stopped believing in anything deeper than our perceived ability to assert control over nature through sheer force of will, and the application of technology. We will come back to this widespread transhumanist impulse in my next post.

Now I want to share the first part of a sample chapter from my forthcoming book about what it means to be human in the "Intelligence Age." Again, the book is organized as a series of expanded ideas about intelligence—different forms of human, non-cognitive intelligence like intuition, imagination, emotional intelligence, and wisdom. This chapter is about what I am calling mortal intelligence. In other words, it's about the importance of developing a healthy relationship to death and dying, how doing so can improve one's life and make one both wiser and more joyful.

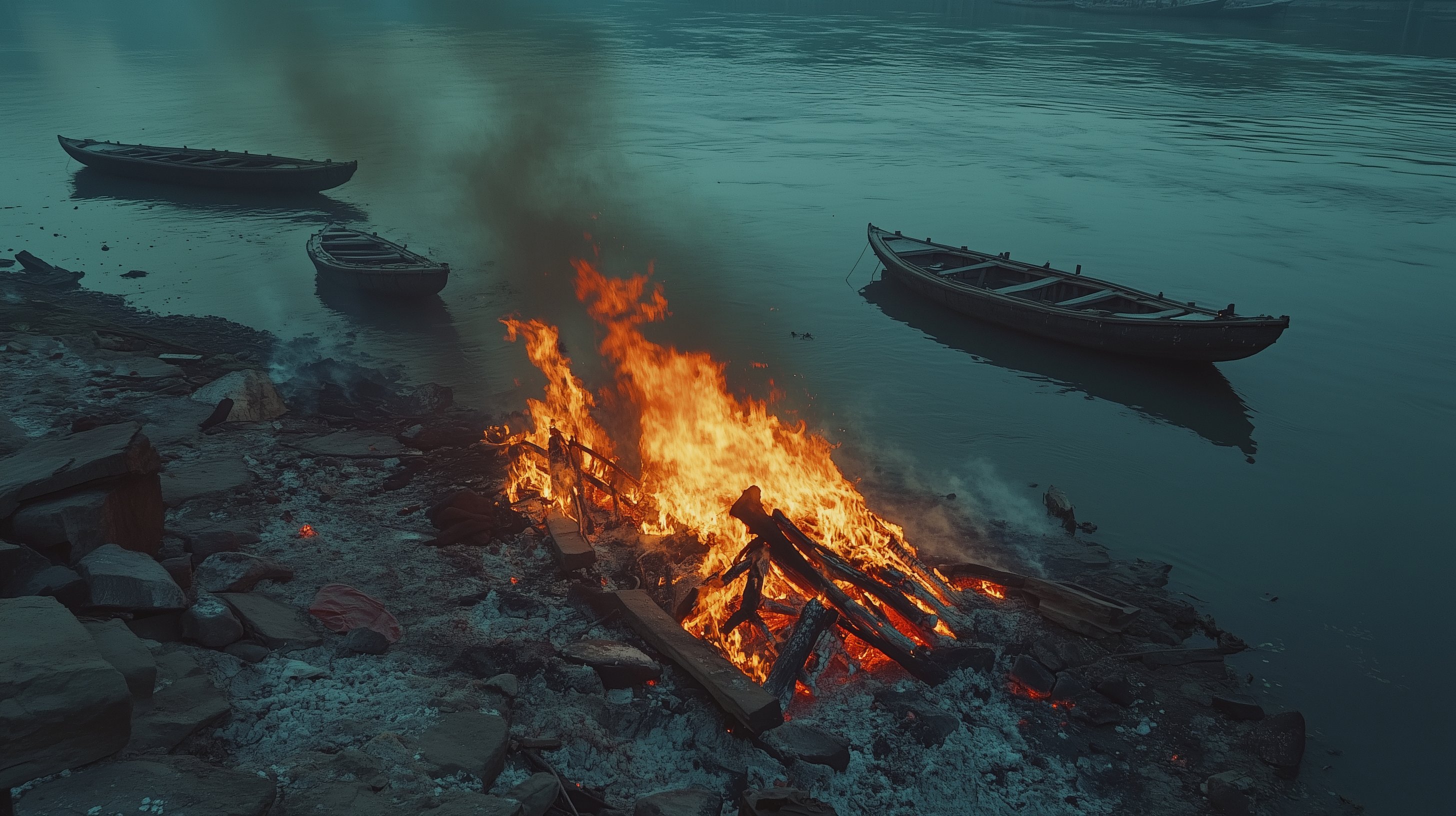

Fiery Death in Varanasi

I watch as they prepare the funeral pyre on the banks of the Ganga River as the sun rises, its rays painting rich shades of orange and burgundy across a blighted sky. The funeral fires here in the holy city of Varanasi burn day and night. On this particular pyre, they use chopped sandalwood, the most expensive choice for rich Hindus. The mourning family emerges from their procession through the narrow, maze-like streets of the city onto the banks of the river, dressed all in white, carrying on their shoulders their deceased loved one wrapped in white funeral cloth. Women are not allowed to participate so the family members are only mourning men trying to put a stoic face on the most existential confrontation with mortality one can have. The story I heard about the absence of women was that female family members used to be present, but would often become so distraught they would throw themselves onto the fire. However, in a highly patriarchal India, it is difficult to know the truth in situations like these.

Before long the wood is lit and the body begins to burn, consecrated flames devouring the lifeless body. Once the flames engulf the body the thing I fixate on is the desiccated feet sticking out at the bottom, occasionally licked by flame, crisping like meat on a spit. This allows me to dissociate somewhat from the full impact of what is happening. But, as I gaze mesmerized, letting my attention fall into the elements, it then connects me more deeply to the raw humanity of what I am witnessing; an accelerated decomposition of the only skin exposed on the dead body. Those particular feet will never tread the earth again.

Half an hour later, a mourning father walks into the river holding a lifeless toddler wrapped in white cloth and submerges the dead body into a river effervescing into mist, rising upwards. To be burned on the banks of the Ganga, one must be at least five years old. At least that is what I was told. Seeing this broken man let go of his lifeless child was easily the most heartbreaking thing I have ever witnessed. The man was absolutely shattered, his face twisted with exhaustion and grief. I have never been so present to the cycle of birth and death. I am filled with awe and gratitude for the eternal gifts bestowed by death in life.

Death is all around me in this bustling Indian city. There is a reverence for it, an acceptance of it. Everyone of all castes and creeds are allowed to witness it, to revere it. Of course, believing that this Hindu ritual guarantees a "good death" and a blessed reincarnation, or even freedom from the cycle of birth and death, elevates it and makes it more palatable. In contrast, in the postmodern, physicalist West, we believe that death is the end, when we allow ourselves to consider it at all.

My days spent on the riverbank in Varanasi were a prolonged meditation on death. Its public nature, even if less emotional, reminded me of the professional wailing mourners of the ancient Mediterranean, or the chanting lamentations of the mekonenet from the Jewish tradition. These ancient rituals, and an honest reckoning with death, allow the bereaved to grieve properly, to do so in community, in public. We could use some of that in the West, with our antiseptic funerals and wakes where we embalm our bodies and our emotions. We have lost sight of the importance of ritual to mark transitions.

There is something life-affirming and even comforting about seeing death acknowledged and even celebrated so publicly. This causes me to reflect on the ways that we hide death in America and other parts of the industrialized world.

Industrialized Medicine and the Denial of Death

Contrast the traditional Indian attitude toward death with that of the industrialized West. As a society, we have a strange relationship to death. We hide it from ourselves and go to great lengths to avoid thinking about it. We see death as a medical and technological failure, aging as a “disease.” Death is part of our societal shadow. In fact, American cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker showed that modern society is “ultimately an elaborate, symbolic defense mechanism against facing our mortality.”

Until the late 1960s, our Western industrialized society “showed an almost complete lack of interest in the subject of death and dying.”2 And not just among the general public but among doctors, psychiatrists, and psychologists. It wasn’t always that way. Preindustrial societies had a healthier relationship to death, inspiring much of their art and enormous monuments to death, such as the pyramids and other enormous tombs and temples, including the 7,000 sculptures at the tomb of Chinese Emperor Qin or the Taj Mahal in India.

Until the nineteenth century, death and dead bodies were encountered in everyday life. For example, as recent as the first decades of the 1800s, upwards of 50 percent of children died before reaching adulthood.3 Average life expectancy at that time was about forty. And it was common practice to butcher one’s own animals in the home.

In contrast, with our factory farming and nursing homes, it is much easier to hide death now. Nobody wants to acknowledge the reality of aging and death, as illustrated recently in the movie The Substance, where an aging Hollywood star takes a mysterious substance to create a younger version of herself. Contrast this with the vaunted role of wise elders in pre-industrial cultures.

Given that most “educated” citizens of the world believe that death is the end, that the self is completely annihilated upon death, it is no surprise that we run from it and hide it, that growing older is denied, postponed, and dreaded.

Fear of death seems to drive the wealthy to clutch at life no matter the cost. Echoing the impulses of Bryan Johnson, many tech billionaires pour millions into immortality projects of various kinds. People like Jeff Bezos, Peter Thiel, Sergey Brin, and Larry Ellison have funded anti-aging companies focused on technological solutions to death.

Unlike problems like poverty and homelessness, death is the one insurmountable hurdle that affects us all. This is why most transhumanists are more concerned with (their own) death than with the kinds of problems they turn away from as they whoosh past the destitute in their self-driving cars. Although there are benefits to this anti-aging research, including improving the quality of life in old age, many of these projects are overly focused on technological solutions to aging, at the expense of public health funding and social support systems.

The Medicalization of Death

As a result of our avoidance of death, doctors and family members don't have the conversations they need to have with patients and loved ones about the moment of death. What’s ironic is that medical advancements that have increased life expectancy make it easier to avoid thinking about and talking about death. Because almost nobody asks their loved ones about their wishes for a good death, we default to quantity over quality. Because the default in today’s materialist, hyper-medicalized world is for medical professionals to assume life extension at all costs, the approach is to use all the tools at our disposal to eek another few months or years out of a life, even if it means being hooked up to machines in a cold, sterile, and lonely hospital room. Families are complicit in this, as are doctors and nurses.

Nearly 80 percent of Americans, when asked how they would like to die, say they would rather be at home with family and friends in a comfortable setting. But, sadly, “only 24 percent of Americans older than sixty-five die at home.”5 Because of our collective silence, 63 percent of Americans die in hospitals or nursing homes, often tethered to machines, alone, and in pain. A mere fifty years ago, most people died at home surrounded by loved ones.6

Not only do most people want to die in comfort at home among loved ones, but they have other priorities besides living as long as possible. Surveys have found that those priorities at end-of-life include avoiding suffering, improving relationships with family and friends, not being a burden on others, being mentally aware, and cultivating a sense of purpose that one’s life is complete.7

Of course choosing a higher-quality, but shorter life is easier when one not only understands the true meaning of death, but has befriended it. We will explore the deeper meaning of death and the power of befriending death in the next post.

Most of us in the modern, industrialized world do not share a nurturing, ensouled cosmology or metaphysics. Instead, we are told from birth by our education system and the media that death is the absolute end — a total annihilation — despite there being no scientific proof of that. In fact, we have extensive proof that consciousness continues in some form after death—it just doesn’t fit into our physicalist worldview. For example, near death experiences (NDEs) that include observation of independently verifiable events have been rigorously documented, yet dismissed as pseudoscience.

Next time, I will explore the transhumanist view of death and immortality, and offer some tips for cultivating a healthier, more spiritual relationship with death, even making death an ally. Imagine that! ☠️

Halifax, Joan, Being with Dying (Shambhala, 1997). ↩

Grof, Stanislav, The Ultimate Journey: Consciousness and the Mystery of Death (MAPS, 2010), 19. ↩

Ebenstein, Joanna, Memento Mori: The Art of Contemplating Death to Live a Better Life (TarcherPerigee, 2024), 18. ↩

Volandes, Angelo E., The Conversation: A Revolutionary Plan for End-of-Life Care (Bloomsbury, 2015), 28. ↩

Volandes, 9. ↩

Id. ↩

Gawande, Atul, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End (Metropolitan Books, 2014), 154. ↩