The Troubling Corporatization of Psychedelic Therapy

An examination of the patent battles and power struggles in psychedelic medicine

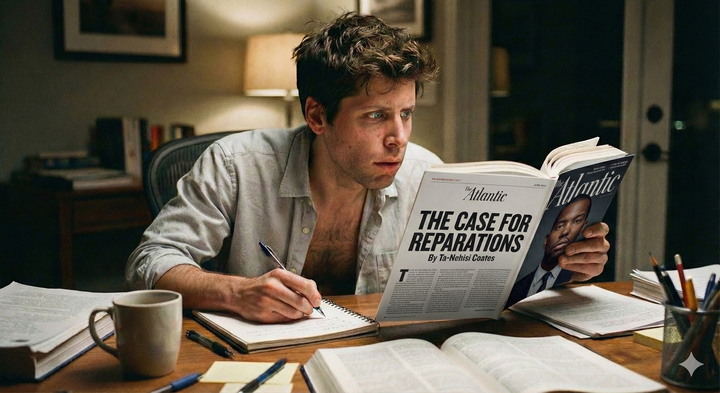

Everyone wants to change the world, especially in the San Francisco Bay Area. These days, one would be hard-pressed to find someone who does not agree that the world needs some changing. Transhumanist billionaires like Sam Altman, Peter Thiel, and Sergey Brin think technology is the solution to all of our problems, and that AI and cyborgization are an integral part of humanity’s future. Each of them has founded or funded a for-profit psychedelic therapy company. Rick Doblin, the founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), thinks the solution to what ails humanity is psychedelics and psychedelics therapy. These oversimplifications illustrate the competing narratives I explore in this post.

You could say that the for-profit companies driven by transhumanist billionaires represent one model for change, while MAPS represents a competing, more egalitarian and idealistic alternative, one hoping to achieve “mass mental health” and a “spiritualized humanity.”1

Psychedelic therapy is experiencing a renaissance at the moment. Because of the unfortunate legal history of psychedelics and their long-standing relationship with the complex forces that have permeated the San Francisco Bay Area counterculture and Silicon Valley, the future of psychedelic therapy is uncertain. For those of us who understand the enormous healing and transformative potential of psychedelic therapy, the corporatization of psychedelic therapy is troubling for several reasons I will explore below.

It is not clear that the for-profit model for psychedelic therapy is the right one to help the most people, for several reasons. But that ship has already sailed. Calls for patent and drug reform are well-intentioned but would require a change in the mindset of policymakers, which seems like a long shot. Given the power dynamics at play, where it seems to be Silicon Valley billionaires versus the more grassroots MAPS approach, what can we do?

Silicon Valley Loves Psychedelics

There have been numerous attempts in recent years to corporatize the administration of psychedelic therapy. This past summer, Google co-founder Sergey Brin announced he is funding a new biotech startup called Soneira that is investigating the benefits of using ibogaine to treat traumatic brain injuries, including filing a patent application for an ibogaine administration protocol that includes electrolytes, an ibogaine protocol that has been used for decades by others. The prior art non-profit Porta Sophia has already challenged the patent Soneira previously obtained for being rendered obvious by prior art. And earlier this year, Rick Doblin, the founder of MAPS, said they were attempting to raise $80 million to secure FDA approval of ibogaine: “We propose to do so in a truly open science manner,” Doblin said, “without seeking patents, and with the intention of immediately making the drug generic.”

Silicon Valley is animated by the belief that everything gets better with technology. And, aside from artificial intelligence, psychedelics seem to be their new obsession. Peter Thiel has invested in Compass Pathways both directly and indirectly through Atai Life Sciences, which owns a substantial stake in Compass. Sam Altman has co-founded Journey Colab, a company offering psychedelic therapy using a synthetic form of mescaline, primarily to treat alcohol addiction. Journey Colab received a patent last month that covers use of its synthetic mescaline derivative combined with long-standing psychedelic practices around “set and setting.”2

According to a Washington Post article titled “Executive behind ChatGPT pushes for a new revolution: Psychedelics,” Altman first identified psychedelic medicine as “undervalued technology” with high profit potential during his tenure as president of Y Combinator, a startup accelerator.

There is a lot of money at stake. As of spring 2023, “companies developing psychedelic drugs or related services have raised more than $560 million in venture capital, according to data provider PitchBook.” That number has increased substantially since last year. In fact, roughly fifty companies in the psychedelic therapy space now trade on public stock exchanges, including those providing psychedelic drug variants, and offering retreats and training programs. Market analysts project the industry could grow to over $10 billion within the decade.

The Risk of For-Profit Approaches to Psychedelic Therapy

As Slavoj Žižek has said, capitalism has the ability to absorb and neutralize all resistance against it.3 Even the most anti-capitalist action or message can become part of a marketing campaign, or a neutralizing meme. For those of us who see enormous potential in the healing power of psychedelics, the burning question is: Will the same thing happen to psychedelic medicine?

There are many challenges with the for-profit model being shaped by big tech. For one, the essential bookends to psychedelic therapy like pre-session counseling and post-session integration will be optimized and automated to such a degree that all humanity and efficacy is sapped, as imagined to depressing effect in We Will Call It Pala.

Next, despite promises from some of the founders and funders of these for-profit psychedelic therapy companies about accessibility and reciprocity, on the whole these proprietary treatments will be expensive and only available to the wealthy. Journey Colab, the Sam Altman company, is taking a two-pronged approach, catering to the wealthy at its Vail, Colorado facility, while intending to serve “marginalized communities,” veterans, and indigenous peoples. Market pressures, competition, and investor pressure will drive prices only higher, at least as long as the various frivolous patents last, which will be almost twenty years. It remains to be seen whether Journey Colab’s promise to serve marginalized communities will become a reality.

Not only that but the success of corporate psychedelic therapy companies will retard necessary drug policy reform by offering a government- and industry-sanctioned option that is blessed as the only "safe" option for those in need, milking the FDA carveouts for “breakthrough therapies” without addressing the larger question of legality. Because these well-connected companies have enormous policy influence and can receive FDA approval for activities that would otherwise be illegal, they have a distinct advantage over grassroots bands of therapists and shamans working primarily underground.

It is difficult to think of another scenario in the history of human civilization where the government has first outlawed a substance and practice and then started granting patents on said substances and practices before their criminal legality has been lifted. This creates all sorts of unnecessary challenges for fairness and public health, including a lack of prior art and expertise at the patent office for methods and practices that have been around for centuries, if not millennia. From the perspective of anticompetitive corporate interests, one would be hard-pressed to imagine a more fertile ground for corporate manipulation.

And then there is the sudden uptick in what seem to be mostly patents that should be invalidated, and represent a form of biopiracy.

The Patent Landscape

Among the largest players is London-based Compass Pathways PLC, which has adopted the conventional biotech strategy of modifying naturally existing psilocybin into a patentable drug and taking it through clinical trials. The firm, founded in 2020, boasted a stock market value of $2 billion in November 2021, but its shares since have slumped 80 percent.

Compass Pathways has filed at least 50 patent claims, prompting its competitors to file more than a hundred patent applications with the U.S. patent office alone. George Goldsmith, the co-founder and executive chairman of Compass, claims an aggressive patent strategy is necessary to ensure that psychedelic therapy will be “available to people across the globe.” This is a common argument made by people ensconced in the venture-capital, Silicon Valley, rapid-growth ethos.

As psychedelic therapy has begun to go mainstream, we should not be surprised to see companies attempt to follow in Big Pharma’s footsteps. And these companies’ patent strategies are understandable given the way venture investing works. VCs expect to see a patent portfolio before investing serious money:

The company’s patent strategy, Mr. Goldsmith said, has been instrumental in coaxing more than $400 million from investors, among them the PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel. Compass is headquartered in London, though its stock trades on the Nasdaq.

The argument proffered by the for-profit psychedelic therapy companies is that patents are a necessary evil to help them create a viable business and cover their costs (including expensive clinical trials). But, given that this is a public health issue, perhaps for-profit business models are not the appropriate avenue. The government is typically tasked with managing resources for the public good, although we do have privatized medicine in the United States.

Of course it also conveniently blocks competitors from entering the space for the duration of the patent. Thankfully, the issued patents only cover synthetic variants of psychedelic plants so traditional therapy and ceremonial usage can continue without patent limitations, if not criminal law restrictions.

Fighting Back

Encouragingly, there are already attempts underway to combat psychedelic patent claims. For example, Carey Turnbull runs Freedom to Operate, an advocacy group that has been challenging bogus patent claims, including those from Compass Pathways.

And Porta Sophia, briefly mentioned above, is attempting to assemble a robust database of prior art in the psychedelic therapy space.

Patent Pledges and Open Licensing

Journey Colab has made a patent pledge, promising not to enforce its mescaline-related patents against people using non-synthetic plants for non-commercial purposes, nor against indigenous communities and practitioners. In addition, in a less formal way, Compass Pathways has promised not to enforce the “set and setting” aspect of its patents, which are likely not enforceable anyway. These efforts go a small way toward addressing the inequities arising from these patent fillings. But they do not change the underlying monopolistic mindset. Nor the imbalanced power dynamics of well-funded, for-profit companies who exert undue influence on the FDA and legislators.

Journey Colab has also established a reciprocity trust, where it allocates ten percent of its initial equity to benefit indigenous communities and other stakeholders in the psychedelic therapy space. It remains to be seen whether this trust actually goes to the designated communities and benefits them substantially.

Patent Reform

Some academics and commentators have called for patent reform in connection with what appear to be patents mostly rendered unenforceable due to obviousness challenges.5 Whether patents are ultimately valid does not reduce the economic and logistical impact for organizations threatened with litigation over such patents and possibly subject to significant financial burden for establishing invalidity.

In any case, calls for patent reform are well and good as far as they go but do not address the larger issues. Bogus patents are more of a symptom of the problem, rather than a cause. Thinking about the pathway to patent reform is a reminder of broken politics and the power dynamics already discussed. What we really need at the government-policy level is a shift in our understanding of the power of these plants; the role of generational trauma in our epidemics of fear, depression, opioid abuse, suicide, and division; and the paradigm shift the plants are inviting us to engage with.

Biopiracy

In addition, Jennifer Seidman suggests that Congress could address the competing goals of reducing biopiracy while promoting access to psychedelic therapy by creating traditional knowledge rights (TKRs) for indigenous groups that have traditionally used psychoactive plants.6 However, despite acknowledging several challenges to this kind of reform, Seidman fails to acknowledge that a majority of Congress today is insufficiently aware or incentivized to consider such legislation. It is an example of the catch-22 inherent in addressing the corporatization of psychedelic therapy more broadly. In order for members of Congress to understand that such reform is needed, they would need to go through a course of psychedelic therapy themselves. That kind of shift is a generation away, at least.

Psychedelic Models for Business

Finally, David Alder calls for “psychedelic models for business,” instead of psychedelic therapy business models. Calling for business to define new standards for integrity, equity and ethics is admirable and necessary. But it suffers from the same catch-22 that calls for policy reform suffer from: business leaders need the kind of mind-expanding experiences offered by psychedelics or other sacred technologies before business can be “reimagined with a technicolor glow.”

Silicon Valley's Transhumanist Ideology

The corporatization of psychedelic therapy is troubling, in part because of frivolous patents and the tendency of for-profit organizations to optimize humanity out of everything it touches by prioritizing efficiency and looking for a technological solution to every problem. It is encouraging to see attempts to combat this trend from academics, organizations like Porta Sophia, and others. But, in my opinion, the larger concern here are the underlying ideologies behind a majority of these efforts.

Why are a majority of these for-profit psychedelic therapy companies funded or founded by members of what academics have called the TESCREAL movement? Peter Theil, Sam Altman, and Sergey Brin all subscribe to some variation of transhumanism, extropianism, longtermism, rationalism, or cosmism. In short, these are ideologies that argue for prioritizing the welfare of future humans and the spread of disembodied copies of their minds throughout the cosmos. These ideologies are confused attempts to channel the inherent human impulse toward meaning and transcendence into technology and economic policy. And they deprioritize the welfare of humans alive in the present, especially those outside the privileged inner circle of Silicon Valley technology leadership.

Neşe Devenot has attempted to draw a connection between the TESCREAL movement and the corporatization of psychedelic therapy, emphasizing its opposition to the welfare of indigenous peoples and its similarities to the eugenics movement. My thesis and emphasis is slightly different: My concern is that employees and customers of these for-profit companies will necessarily buy into the transhumanist ethos of their funders and founders. Whether overt or covert, we should expect these companies to hire and train therapists and facilitators to further the simultaneously eschatological and apocalyptic scientific materialism of the transhumanists.

In short, when it comes to psychedelic therapy, worldview matters enormously.

Psychedelics Are Not a Panacea

Although they have been shown to increase openness, psychedelics alone do not guarantee the expansion of consciousness or a positive evolution of worldview that benefits all of humanity. The ideological, philosophical, and metaphysical backdrop matters immensely. We see this with cults like the Manson family and the rise in popularity of microdosing to boost productivity within the Silicon Valley knowledge worker community. The naturally increased openness primes psychonauts for whatever worldview or ideology they are exposed to following psychedelic experiences. As Stan Grof said, psychedelics are “non-specific amplifiers” of mental processes. And, context determines experience. R. Gordon Wasson, Timothy Leary, and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) sought mystical transcendence in psychedelics and found it. Indigenous people sought healing and found it. This is why MAPS and ayahuasca retreat centers with integrity offer such robust post-therapy or post-ceremony integration.

Like technologies of the mundane, psychedelics are not a positive engine for change on their own. Psychonauts require community support and holistic integration.

The Importance of MAPS

Rick Doblin and MAPS spent decades laying the groundwork for the current renaissance in psychedelic therapy. In contrast with the profit-maximizing, corporate ethos and materialist, science fiction ideologies of the transhumanists driving the corporatization of psychedelic therapy, MAPS offers a more accessible path to mass adoption and lasting policy change. In addition, Doblin sees psychedelic therapy as essential to achieving “global consciousness change” and a “spiritualized humanity.”

Not only that but MAPS has a long-standing partnership with the Center for Psychedelic Therapies and Research at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS).

CIIS created the Center for Psychedelic Therapies and Research in 2015.

Top psychedelic researchers and scholars work with the Center to teach in the certificate program, mentor trainees, and sit on the Center’s council of advisors. This includes a history of collaboration with MAPS PBC, the Heffter Research Institute, and the Usona Institute, three of the most renowned research organizations for psychedelic studies. The Center’s certificate program is the largest collaborative program focusing on psychedelic studies within a non-medical graduate university.

Although, despite Doblin’s stated vision for the future, MAPS does not proselytize a specific metaphysical worldview in its work, its affiliation with CIIS means that the backdrop for its work in the world is more ensouled and philosophically enlightened than that of the transhumanists and the for-profit companies I have surveyed above. For example, the learning goals of the philosophy, cosmology, and consciousness program at CIIS include a critical examination of the causes of what Joanna Macy calls “The Great Unraveling,” including anthropocentrism, the patriarchy, the mental ego, and capitalism, to “analyze the current devastation of planetary life and to strive to liberate ourselves and our communities from the underlying causes of alienation, consumerism, androcentrism, racism, and unsustainable modes of life.” This vision necessarily infuses the work that MAPS does in collaboration with CIIS and the Center.

Again, rather than merely paying lip service to accessibility and reciprocity, MAPS is actively working toward making these therapies accessible to the largest number of people, regardless of means. The MAPS integration protocol is holistic, robust, and relatively ideologically neutral, emphasizing six domains: mind, body, spirit, lifestyle, community, and nature.

Conclusion

The psychedelic renaissance is an exciting opportunity, and a profound turning point in the history of humanity. This is why its shape and direction are so important. The corporatization trends emerging in the past few years, and the influential figures driving those trends, present enormous challenges, including challenges around accessibility. While efforts to combat excessive patent claims and promote reciprocity are encouraging, they do not fully address the underlying issues of power dynamics and conflicting worldviews.

The MAPS approach, grounded in a more ensouled worldview and a commitment to accessibility, offers a promising path toward mass adoption and lasting policy change. By prioritizing holistic integration, community support, and a focus on healing generational trauma, MAPS provides a model that honors the transformative potential of psychedelics while remaining mindful of the ethical and social implications of their use. It is not perfect. And I think part of the solution here is increased education about the nature of psychedelics and psychedelic therapy, as well as more media coverage of the ideologies driving Silicon Valley investment and innovation, which is part of why I am writing a book about these transhumanist, cyborgian ideologies.

One might argue that favoring the MAPS worldview and trusting Rick Doblin’s mission over the transhumanist worldview of the Silicon Valley billionaires is an arbitrary choice between two utopian visions for the future, that this argument amounts to so much hair splitting. However, I maintain that it matters deeply because the MAPS view seeks the greatest good for the greatest number while the transhumanist view seeks to create a cyborg race of humans that can escape the deteriorating earth for the stars, leaving most of us to languish in a worsening climate as a small price to pay for the welfare of the future of the cosmos. This debate is about grounded desire for real healing and change in the present versus science fiction fantasies driven by the unresolved angst that one always finds with traumatized adherents of scientific materialism.

Despite the outsized influence of people like Sam Altman and Peter Thiel, I remain optimistic that the plants will have the final say in the long-run. They always have.

Rowland, Katherine, “Thanks to This Man, MDMA Could Soon Be Legal for Therapy,” The Guardian, February 29, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/feb/29/mdma-therapy-legal-rick-doblin. ↩

Chowdhury et al., Methods of Treating Substance Use Disorders Using Mescaline, US 2024/0245632 Al, filed May 27, 2022, and issued July 25, 2024. ↩

See Fisher, Mark, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Zero Books, 2022); The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, Documentary, 2012, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2152198/. ↩

Marks, Mason, and I. Glenn Cohen, “Patents on Psychedelics: The Next Legal Battlefront of Drug Development,” Harvard Law Review, 2022, 231, https://harvardlawreview.org/forum/no-volume/patents-on-psychedelics-the-next-legal-battlefront-of-drug-development/. ↩

See, e.g., Marks, Mason, and I. Glenn Cohen, “Patents on Psychedelics: The Next Legal Battlefront of Drug Development,” Harvard Law Review, 2022, https://harvardlawreview.org/forum/no-volume/patents-on-psychedelics-the-next-legal-battlefront-of-drug-development/; and Seidman, Jennifer, “Tripping on Patent Hurdles: Exploring the Legal and Policy Implications of Psilocybin Patents,” Cornell Law Review, 2023, https://www.cornelllawreview.org/2023/07/25/tripping-on-patent-hurdles-exploring-the-legal-and-policy-implications-of-psilocybin-patents/. ↩

Seidman, 1035. ↩