The Better AI Gets, the Further We Seem from AGI

An honest survey of the AI field and an appreciation for the mystery of human intelligence

Remember in 2024 when Sam Altman said OpenAI had a clear roadmap to AGI in 2025? Or when Anthropic’s Dario Amodei predicted in 2024 that we would have a “country of geniuses in a data center” by 2026? Way back in 2023, Ilya Sutskever seemed to think that AGI was right around the corner as well.

It’s 2026 and we don’t seem to be any closer to AGI or superintelligence than before, despite what the major AI labs have been telling us, and despite so much of their valuation (and the U.S. economy) hanging on these promises of general intelligence. So I thought I would take this opportunity to examine where the industry is on their ambitious march toward some kind of machine messiah, and use that as an opportunity to discuss intelligence more broadly.

In the summer of 2024, I put together a comprehensive summary of what I saw as the impediments to reaching AGI, including hallucination, a lack of common sense, and a failure to understand cause and effect. In this post, I want to revisit a few of those impediments as we enter 2026, ending with the mystery of abductive reasoning.

Before we dive in, let me highlight one eye-popping tidbit:

- OpenAI seems to be valued at around $830 billion. Normal software companies typically trade at 8x to 12x their revenue. With about $20 billion in annual revenue, OpenAI is valued at 41.5x its revenue. That enormous markup is tied to their promise to be creating AGI soon. (Anthropic’s is around 35x revenue.)

In other words, the AI bubble is all about AGI, although OpenAI seems to have changed its tune, promising to build a digital employee instead of a digital god. In short, if the AI companies weren’t promising to disrupt the very nature of the economy, capitalism, and human society itself, they wouldn’t be valued so highly.

Whether the AI labs manage to create an omnipotent machine god who will “solve all of physics“ (Altman’s phrase, whatever that means) or simply replace the workforce with robots, these are deeply destabilizing visions of the future. Honestly, I think we’re all being pretty chill about it, especially in light of the fact that nobody seems to have a viable plan for what happens after the supposed earth-shattering disruption being promised by OpenAI and the other AI labs.

Who Is Qualified To Opine on the Nature of Intelligence?

By the way, isn’t it funny how we have all accepted the idea that computer scientists are experts on the topic of intelligence? What qualifies a person trained in writing computer code to opine on the nature of human intelligence? When I was doing AI research as a computer scientist in the 1990s, I too felt qualified to know what intelligence is, despite having no training in cognitive science or philosophy (although now I do have a master’s in philosophy, cosmology, and consciousness). I think this has something to do with the long-standing assumption in our culture that the mind (and the rest of nature for that matter) are computable—meaning that the brain simply manipulates symbols, making it easily reproduced in silicon and software—even though it is not at all clear that it is.

Anyway, let’s examine the AI landscape and its implications for our broader understanding of the nature of intelligence. That will then allow me to talk about other human faculties beyond cognitive intelligence in greater depth in future posts.

A note on AI model terminology: 2025 has seen the rise of natively multimodal AI models like Gemini 3 and ChatGPT 5 (meaning they can handle images, audio, and video natively). Because they are multimodal from the ground up, they are Large Multimodal Models (LMMs). But they share the same underlying transformer architecture as Large Language Models (LLMs). Because it is slightly more accurate, I will use the term LMM or “foundation model” to refer to models like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude, rather than LLM.

The State of AI

In 2025, the AI industry evolved from simple chatbot AI like ChatGPT to “reasoning“ models and took baby steps toward agentic AI. It also began to acknowledge the need for new approaches to artificial intelligence, including the need for world models, neuro-symbolic hybridization, and even basic research into the nature of intelligence. More on all of this in a moment.

Long-time AGI skeptics like Gary Marcus and more recent converts like Yann LeCun (formerly Chief AI Scientist at Meta) have argued that large language models are not sufficient to get us to AGI or superintelligence. As we have seen, the state of AI at the end of 2025 bears this out.

Remember, the current approach to AI (machine learning) assumes that the mind, and therefore intelligence, arises from the firing of neurons in the brain. Predicated on this conjecture, foundation models like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini are enormous software simulations of neural networks that attempt to recreate the way the brain works in silicon. But nobody knows for sure that the mind or consciousness arises from the brain. It’s just a theory.

For me and the other long-time AGI skeptics who have been pointing out that machine learning models are not nearly enough for true intelligence, Sutskever’s admission sounds absurd. Shouldn’t understanding intelligence have been the starting point in AI research?

Nevertheless, AI developers are confident that they have basically solved intelligence and will soon create “superintelligence.” They just need bigger, faster machines and more training data (and a lot more money). In other words, it is simply a question of “scaling.” When I was a computer engineer, I thought like this too; it’s how we computer scientists are educated: The brain is an organic computer and intelligence is computable; intelligence is no big deal.

The Age of Research

Ilya Sutskever recently told Dwarkesh Patel that the AI industry is moving from the Age of Scaling to the “Age of Research,” meaning research into what intelligence actually is. In other words, calling into question the longstanding gospel that scaling large language models (adding more data and processing power) is enough to get us all the way to superintelligence, as if intelligence was simply comprised of language produced by modern man. For me and the other long-time AGI skeptics who have been pointing out that machine learning models are not nearly enough for true intelligence, Sutskever’s admission sounds absurd. Shouldn’t understanding intelligence have been the starting point in AI research? It’s a good reminder that one of the major themes of AI research since its inception in the 1950s is unbridled hubris. More on the topic of the relationship between language and intelligence below.

In any case, it’s nice to hear a major AI researcher warm to the idea of approaches beyond simply scaling LMMs, especially given Sutskever’s prior hubris.

Sam Altman has also called our present moment the “Intelligence Age.” Maybe we’re all exhausted because we’re living through so many ages at the same time!

Today’s machine learning models like ChatGPT and Gemini consistently run up against Moravec’s paradox, where AI models excel at PhD-level intelligence tests but fail to successfully count the number of r’s in the word strawberry, fold a t-shirt, identify a wet spot, or understand object permanence. It’s a good reminder that today’s AI models aren’t actually reasoning; instead, they are performing multiplication on very large sets of numbers to produce new numbers that are then translated back to text, images, sound, or video. In contrast, when you think through the steps involved in solving a Rubik’s cube, you are thinking spatially, in terms of colored squares on a piece of plastic in your hands. Or when you fold a t-shirt, you are usually not thinking about it at all but simply allowing your hands to perform a series of motions involving interactions with cloth that reflect a lifetime of folding and interacting with clothes, an embodied knowing that is a function of your having a body and having lived experience.

Machines exhibit a kind of thin and brittle intelligence, one founded upon human language. But not so much language as chunks of words reduced to numerical values. In this elaborate number-crunching process, the machine does not understand the words that it is processing. It simply combines words in ways that seek to follow rules and satisfy design parameters. As researchers have recently shown, these models are simply memorizing the text that they train on and remixing it in novel ways, something AI developers refer to as “lossy compression,” meaning that AI models are simply storing an imperfect copy of the training data.

In contrast, humans exude and are permeated by a rich spectrum of intelligences, most of which we don’t think about much, or understand—for example, emotional intelligence or embodied intelligence. I will be exploring these other intelligences or human faculties in the forthcoming posts.

Persistent Impediments to AGI

Let’s review some of the impediments to AGI that I discussed back in 2024: hallucinations, common sense, and a general lack of understanding of how the world works.

Hallucinations

Today’s AI models notoriously hallucinate, or just make shit up. I’m not a fan of the use of the word “hallucination” for this tendency that AI models exhibit. After all, hallucination is what human minds do as a result of their mysterious, phenomenological nature (a topic outside the scope of this post). So it is an ill-fitting metaphor. Nevertheless, it has become the standard nomenclature in the AI context so I will use it here.

As we have already seen, AI models don’t “know” facts; they only recognize patterns in text, imagery, or audio. ChatGPT doesn’t know, for example, that Paris is the capital of France. When it responds to the question, “What is the capital of France?” it is saying “Paris” because most of the time it has come across a sentence about France in its training data, Paris has been named as the capital.

Another way to say it is that AI models don’t store information in a file or database. Instead, it stores a numerical approximation of that information that it then attempts to approximately reconstruct when asked.

AI systems are also designed to please the user so they may agree with an incorrect assertion in order to satisfy the user. If you ask when Al Gore invented the internet, it may reply, “Al Gore invented the internet in 1993,” despite the fact that he didn’t because of a longstanding joke and because these AI models don’t always understand irony and humor.

Fortunately, LMMs have improved slightly in terms of factual reliability, not because they understand the world or have common sense, but because the AI labs “ground“ them in reliable sources and they are hooked up to specialized tools for performing computation, like math.

Granted, intelligent humans also lie and get facts wrong. So maybe expecting more from AI systems is unfair. After all, the ability to discern truth from fiction is more a function of wisdom than intelligence. Although I wrote a post about this last year, I would like to return to the topic of wisdom in a future post.

Common Sense

Common sense is a large topic that leads into a number of other topics well beyond the scope of this post. It has something to do with moving through the world in a body with a nervous system and all the knowledge that arises from that, including an intuitive understanding of physics, quantity, object behavior, and theory of mind—what other beings may be thinking.

The amorphous nature of common sense is a reminder that intelligence isn’t a calculation; it’s a dynamic relationship with the physical and social world.

Also, the thing about common sense is that it’s largely the knowledge that humans have about the world that is so obvious that it is rarely written down. In that way, it is not something you could train an LMM on through recorded material. Which brings us to the topic of language and its attenuated relationship to intelligence.

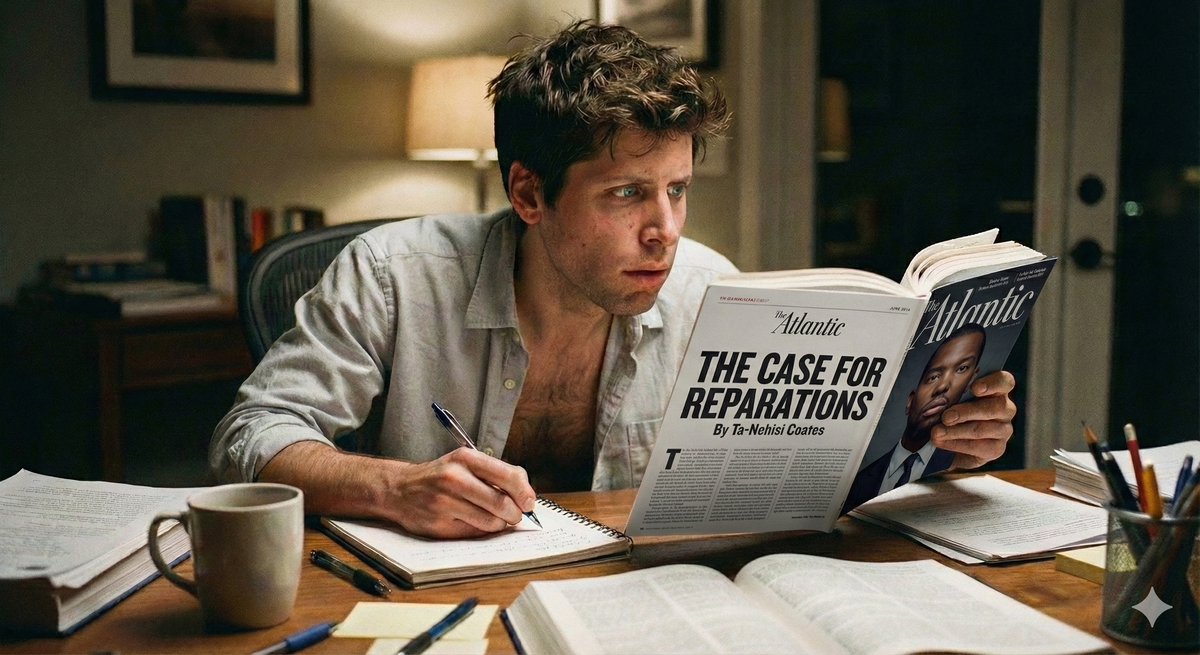

Word Worship

When you stop and think about it, it seems odd that leading AI researchers and cognitive scientists see language as the basic building blocks of intelligence, despite the fact that humans developed language primarily to communicate (rather than think) fairly recently (50,000 years or so ago). Intelligence is much older and deeper than mere language.

In the words of a neuroscientist, a linguist, and a cognitive scientist in a 2024 commentary published in the journal Nature, although language facilitates the transmission of cultural knowledge, such linguistic capacity merely reflects the pre-existing sophistication of the human mind. Language does not constitute or undergird intelligence.

Although we often do think using language, language appears to have arisen and then evolved for the purpose of communication, not thought. In that sense, language reflects the sophistication of human thought, rather than being a fundamental building block of it.

Neuroscience has shown that reason is largely independent of language. We humans use language to express our internal thought process and mental state, and we often think in terms of language. But language and thought are not synonymous. We just live in a word-obsessed culture.

LMMs are simply tools that emulate the communicative function of language, not the separate and distinct cognitive process of thinking and reasoning, no matter how many data centers we build.

We can verify this scientifically by looking at fMRIs of people solving math problems or engaging in “theory of mind”: Non-linguistic areas of the brain light up in those cases. In other words, the brain’s language network is distinct from networks that support thinking and reasoning. In fact, as the authors of that Nature commentary point out, people who have lost their linguistic capacities as a result of brain damage—a condition known as “aphasia“—are still able to reason, solve math problems, understand the motivations of others, and make complex plans.

You can further verify this decoupling of reason from language by observing a toddler or an animal. They are clearly able to reason about the world and make plans without the use of language.

According to the authors of that Nature article, language is not only unnecessary for thought but it is insufficient for thought. There are brain disorders, for example, where the person can sound quite articulate while the ability to reason is impaired. As we see with LMMs, a facility with language does not necessarily reflect actual comprehension. But it does create a believable illusion because, in our society, being articulate has been a proxy for intelligence. Of course we can point to many public intellectuals who are widely considered highly articulate yet do not appear to evidence much intelligence.

In short, being articulate is an unreliable signal for intelligence. Language is not thinking, although writing can be a useful exercise in clarifying one’s thinking.

As we see with LMMs, a facility with language does not necessarily reflect actual comprehension. But it does create a believable illusion because, in our society, being articulate has been a proxy for intelligence.

One attempt to address the pure language critique and to take a small step toward developing common sense is world models and spatial intelligence. Many of the AI training challenges seem to arise from a general lack of embodiment, especially in the AI training. And it appears that the most valuable kind of embodied AI training would be multi-sensory; not just vision but hearing and even tactile sensing and proprioceptive adaptation.

World Models and Spatial Intelligence

Obviously, disembodied algorithms trained on language and media alone will never learn to navigate or understand the world. At the very least, they will need to interact with and experience the world. But training robots in the real world is expensive, slow, and dangerous. So the current approaches train simulated robots in simulated environments.

Yann LeCun, former chief AI scientist at Meta, has been calling LLMs (or LMMs) an “off-ramp” to AGI since about 2022. He thinks that the missing piece is world models and spatial reasoning or spatial intelligence: the ability to understand physics and cause-and-effect in 3D space. LeCun’s JEPA project trains on millions of hours of YouTube videos combined with a small amount of robot interaction data.

Similarly, Fei-Fei Li’s startup World Labs, launched a multimodal world model late last year: Marble creates a consistent 3D simulation with internal physics. Although these projects rely primarily on simulation, perhaps they are a step in the right direction. Looking beyond simulation-based world model training, Google’s research into using robotics to train world models might be most promising, although it is fairly limited to date, focused on robot arms sitting atop tables.

As I argue in my forthcoming book and will discuss in future posts, intelligence is embodied to a greater extent than we think. Having five senses that are connected to a biological central nervous system may be essential for human intelligence. I argue that, from an evolutionary and even metaphysical standpoint, smell, taste, and touch are not superfluous niceties but an integral part of the package.

So, although these world models might go part of the way toward helping AI models understand cause and effect, they will get us nowhere near AGI or superintelligence. They may even give AI systems a certain level of common sense, although I think that too is more mysterious than we think, having something to do with intuition, emotional intelligence, embodied intelligence, and abductive reasoning.

Let’s take a brief look at that last one.

Neuro-Symbolic AI and Abductive Reasoning

Current AI systems like ChatGPT or Gemini are modeled primarily on one kind of human intelligence: inductive reasoning. This is a form of “bottom-up” reasoning that draws conclusions from specific observations. For example, if you’ve only ever seen white swans you conclude that all swans are white. That’s inductive reasoning. In prior AI eras from the last century, AI systems were modeled on deductive reasoning, a “top-down” approach that starts with general statements about the world and applies them to specific instances: To use a famous example, we might say that all men are mortal. Then, if Bryan is a man, we know he is mortal.

has long argued that AGI will require a hybrid approach combining the neural-network machine learning that’s so popular today (induction) with the more top-down symbolic reasoning of older AI systems (deduction), to create what’s known as neuro-symbolic AI (NeSy).

Google DeepMind has a long history of using hybrid approaches to machine learning in specific applications like AlphaGo. And they have been applying a more explicitly NeSy approach in domains like mathematics with AlphaGeometry and AlphaProof.

In short, NeSy is an attempt to model two modes of thinking that humans engage in: deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning. But there is a third, more mysterious kind of reasoning called abductive reasoning that is harder to model, but may be crucial for achieving true AGI.

As I explained in my impediments to AGI video, abductive reasoning is defined as an inference to the best possible explanation. It’s the intellectual leap that detectives and doctors make, from a set of facts to a plausible explanation. A detective is not thinking logically, step-by-step through the problem, examining every possibility. The explanation simply emerges wholesale in her mind.

The quintessential example is Sherlock Holmes. For example, in The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor, Holmes was able to locate a missing woman who disappeared at her wedding from a few conversations, and a hotel receipt, based solely on his understanding of human behavior and knowledge about “what people generally do.”

Abductive reasoning seems to combine common sense, knowledge of the world, and some amount of creativity and intuition. It also requires both induction and deduction: induction to identify patterns and deduction to test the hypothesis.

Although nobody knows how abductive reasoning works, some AI researchers think that having a reliable world model is one step toward being able to reason to the best possible explanation: For example, an AI system would more reliably be able to reason that because a glass is broken it probably fell.

Cognitive scientist and philosopher Jerry Fodor thought that in order to perform abductive reasoning, a system would have to draw on everything it knows about the world. Because this seems to happen in an instant without any belabored reasoning but rather a flash of insight in humans, it’s not clear how to model it in a machine.

Philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, who first studied, formalized, and named the concept of abduction, ultimately concluded that abduction is some sort of instinct, calling it “the light of nature.” However, I’m not sure that’s exactly right; I think it may arise from the same mysterious imaginal realm from which creativity arises.

The mysterious nature of abductive reasoning in particular is why cognitive scientists and philosophers refer to it as the “dark matter” of intelligence. And yet the major AI labs pretend as if it doesn’t even exist, that induction is all there is to intelligence. If world models are any kind of solution here, I will be watching the work of Li and LeCun very closely this year.

If you’re curious to learn more, I produced a whole video a few years ago about how non-ordinary states of consciousness may give us some clue to abduction’s origin in the mind.

Conclusion

The more time that passes since ChatGPT exploded onto the scene and AI CEOs started promising the imminent arrival of AGI or superintelligence, the more it becomes apparent that intelligence is deep and mysterious and that we are nowhere close to any kind of superintelligence.

Notice how many impediments still remain to achieving AGI. And yet the leaders of the AI labs would have us believe that we are on track to AGI. This disconnect is why I think a bursting AI bubble is imminent.

What does that mean for the valuations of the AI companies like OpenAI and NVIDIA? What does it mean for the economy, and for humanity?