How Do We Know Other Beings Are Conscious?

An exploration of conventional and unconventional answers to questions about human, animal, and machine sentience

With artificial intelligence and the global sprint to AGI, this is the first time humanity is trying to use technology to enter the realm of consciousness, although you could argue that quantum physics was an inadvertent entry into that mysterious realm a century ago. Whether AI researchers realize it or not, suggesting the possibility of conscious machines is forcing us to reconsider the metaphysical assumptions of science, and inviting us to bring philosophy back into the mainstream conversation.

Let me explain.

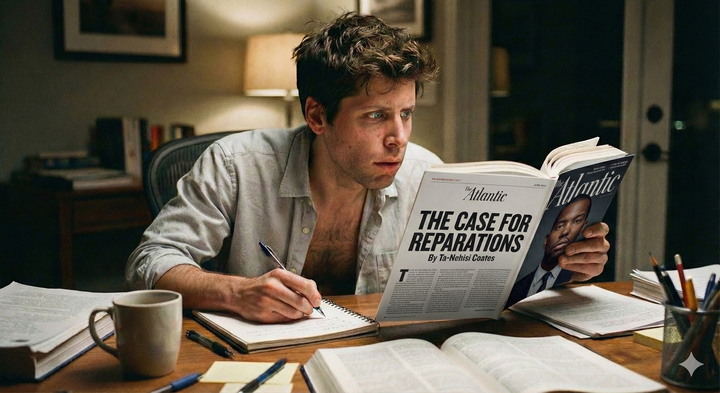

In my last video, in response to Anthropic hiring its first "AI model welfare" researcher, I talked about how unlikely it is that current AI systems will become sentient. I received a number of thoughtful responses, a lot of them asking how we know that anything is conscious. Given how little science knows about consciousness, people asked, isn't talking about it kind of pointless?

People also called me a "robophobe," which is a wonderful neologism. I'm not afraid of robots though, just the real-world harms introduced by technology innovation driven by dehumanizing ideologies like transhumanism.

So, perhaps in talking at length about the slippery question of consciousness we will gain some clarity. At the very least, we will come to appreciate the magnitude of the challenge in attempting to create sentient machines.

In entering the realm of mind and consciousness, AI companies are attempting to tackle the most profound questions ever posed, but approaching it as if it is an engineering problem rather than a question of philosophy or metaphysics. It is a simple matter to manipulate nature into gadgets. But Silicon Valley has moved on from gadgets. It is the age of intelligence after all.

The success of technoscience in giving us technological advances over the past few centuries has tricked us into thinking that everything is easy, that everything amounts to an engineering problem. But making a conscious being is an entirely different matter from making a smartphone out of sand, precious minerals, and electricity.

Conventional Answers

As I attempt to answer this question about consciousness, first I will explore the conventional approaches to answering it, and then I'll consider a more novel and elegant perspective that comes from both Western and Vedic philosophy.

Remember, we're talking about the third kind of consciousness I defined in my last essay: phenomenological consciousness—the experience of what it is like to be you.

The Argument from Analogy

The first conventional answer is an argument from analogy. You have a mind, and subjective, qualitative experiences that result in behaviors like smiling, crying, and talking, which correlate to inner states like happiness, sadness, and imagination. And you can observe other humans (and animals to some extent) with similar behaviors. Therefore, you can infer that other humans are conscious.

The alternative—that you're the only human (or animal for that matter) with these rich, subjective experiences, that other people are "NPCs"—is narcissistic and even sociopathic.

What about verifying consciousness by measuring brain activity with an electroencephalograph (EEG)? That doesn't help us much either. It's true that there is a strong correlation between brain activity and conscious activity. But that is not necessarily evidence of subjective conscious experience. Brain scans of people on psychedelics or in deep meditative states sometimes show little to no brain activity, despite the person having the most vivid psychedelic experiences. Conversely, there can be measurable brain activity without any subjective experience, as in the case of sleep stages where there is no dreaming, anesthesia-induced unconsciousness, and subliminal perception that does not enter conscious awareness.

Organizational Invariance

A similar approach is this notion in philosophy popularized by David Chalmers called "organizational invariance." This theory argues that any two systems with the same fine-grained functional organization will have qualitatively identical conscious experiences. So, under this theory, two human brains must have similar capacities for subjective experience. Of course, as any yogi or Buddhist will tell you, the quality of the actual experience will depend on the relative state of consciousness.

Under this theory of consciousness, the organizational structure must be fine-grained and functionally identical. So it's not enough to create a software simulation of the rough nodal arrangement of neurons. The invariance would have to go down to the level of molecules at least, and may require a physical structure beyond software. As philosopher Bernardo Kastrup puts it, creating a detailed simulation of kidney function in software on my computer will not cause my computer to urinate on my desk.

Abduction: Inference to the Best Explanation

Another way to find consciousness with other beings is through abduction, which I talked about at length in my essay on intelligence and AGI. When it comes to living beings, a rich internal world is the best explanation for the complex, meaningful, and purposeful behaviors they exhibit. When we see a person crying it is likely because they are experiencing the emotion of grief or sadness, not because they are running some artificial crying algorithm.

This obviously gets trickier with robots and AI systems. Then, the inference goes the other way, or becomes unreliable. Here, we require discernment. Given what we know about the construction of AI systems and robots, the inference we would make in the case of a robot is that it probably is running a simulation of emotional responses.

This highlights the limitation of abductive inferences: They must eventually be verified with deductive reasoning. This also points to the limitations of the conventional approaches to verifying the presence of consciousness. By fundamentally misunderstanding the nature of consciousness and even reality itself, they can only ever make guesses. More on that in a moment.

What About Animals?

What about animals? Philosopher René Descartes thought animals were essentially robots. But we can apply most of the conventional approaches discussed above to animals: Animals play and grieve and experience fear. So arguing from analogy or inferring to the best explanation, it seems plausible that they too have subjective, qualitative experiences.

Not only that but many animals have complex brain structures, especially the larger mammals. So organizational invariance points to animals having rich internal experiences too.

Finally, humans evolved from primates and lower animals so that would suggest a sort of continuum of consciousness that just keeps expanding as you go up the evolutionary chain.

Still, there is a simpler, more elegant answer for all living beings. So let us approach this question from the other direction. Instead of looking at structures and behaviors, what if we accepted a different, more elegant metaphysics? After all, the one we've got—scientific materialism—can't seem to explain, or confirm, consciousness.

Philosophical Idealism & Universal Consciousness

The predominant worldview that most of us are born into says that matter — or, after Einstein, matter/energy — is fundamental. Under this view, the nature of reality is fundamentally material. This view is called physicalism, or scientific materialism. But it is a relatively new worldview and, in the grand sweep of human history, a minority view.

It may come as a surprise to you that there have been a number of philosophical schools over the millennia that have proposed that mind or consciousness is fundamental, rather than matter.

These include various forms of Hinduism or Yog-Vedanta like classical Tantrik yoga, at least one strain of Buddhism known as Yogacara Buddhism, and, from the Western tradition, analytic idealism.

What does it mean for consciousness to be fundamental instead of matter? It means that everything that exists, including your furniture, your iPhone, your body and your brain exist within this universal consciousness, and are made of consciousness. Their seeming solidity is simply a function of the interaction between differentiated consciousness. The structure and patterning of universal consciousness is, after all, still the laws of physics. And we share the same reality because we are all small pieces of mind inside of universal mind.

Fortunately, universal mind seems to be very good at remembering where things are. If you leave your stapler on the desk, the consciousness that is that stapler is still there unless something moves it.

This alternative view doesn't change physics; it only changes what is valid subject matter for scientific exploration. For example, maybe near-death experiences (NDEs) suddenly become scientifically accepted. Or telepathy, or telekinesis. I'm not expressing an opinion about those phenomenon—they're just examples of how the scientific worldview prematurely rejects certain things for being "superstitious" or "supernatural," simply because they don't fit into the strictures of physicalism, which is founded on a series of assumptions in the first place.

Just like there is something that it is like to be you, there is something that it is like to be universal consciousness. Of course we can't comprehend what that experience is like. But the Vedic or Tantrik view is that it is fun for universal consciousness to partially forget itself and to become these finite expressions of its infinite nature.

Typically some sort of water analogy is used to paint the idealist picture: The cosmos is like a great ocean and living things are waves upon that ocean—temporarily separate but never fully separate. Or, the cosmos is like a great river and we are all eddies or whirlpools in that river, temporarily self-reflecting for a time.

I realize that all of this takes a moment to wrap your head around. Because it's so foreign, so bizarre. That's because we've been acculturated to thinking in materialist terms. If we had been born into an idealist culture, it would seem perfectly natural.

How does this mind-bending view of reality help us answer the question about the consciousness of other beings? In idealism, our bodies and brains are what our little piece of consciousness looks like from the outside. Pause and take a moment to contemplate that. When you look at other people you might be seeing a persistent, yet changing, manifestation of their temporal eddy of universal consciousness instead of a clump of material somehow animated into a thinking, feeling miracle.

We think AI systems can become conscious because physicalism and technoscience tells us that nature, life and even consciousness are machine-like, computable. With that line of thinking, if nature and life are mechanistic, then creating a new form of sentient life is simply a question of computation, or "compute" as the AI companies like to say.

Life Is Conscious

Within idealism, when universal consciousness separates into these tiny finite expressions, that's life. In other words, life is what individuated consciousness looks like within universal consciousness.

In short, life arises out of consciousness, within consciousness.

Not everything has a subjective experience. There is nothing it is like to be a rock or an iPhone. They are not biological. Instead, in the river analogy, rocks and iPhones are tiny ripples on the river—patterns within universal consciousness, not conscious, self-reflective whirlpools.

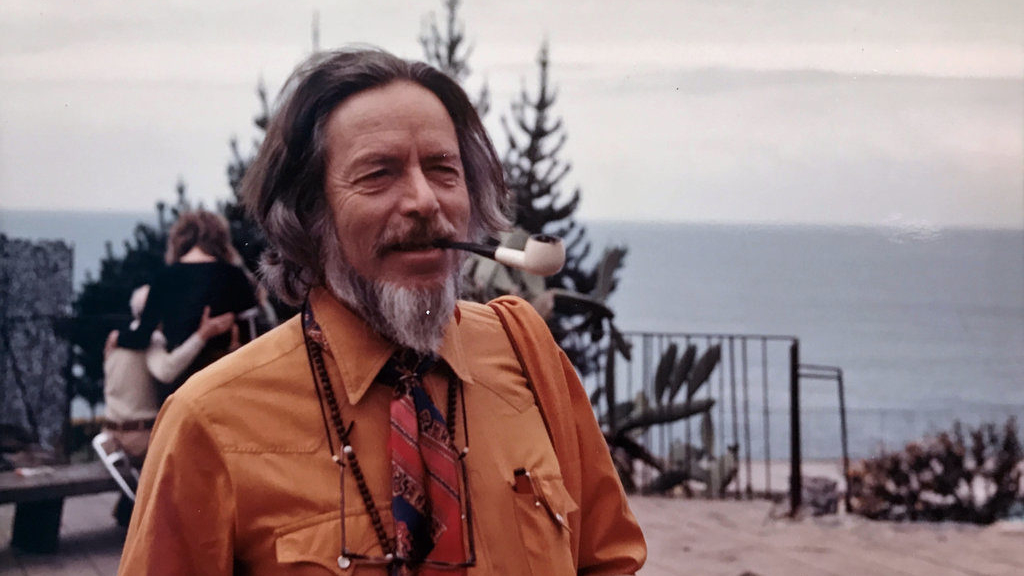

So, within idealism, we know living beings are conscious because they are small pieces of universal consciousness. Or, as Alan Watts put it:

We do not 'come into' this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean 'waves,' the universe 'peoples.' Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature, a unique action of the total universe.

Maybe this sounds too mystical or supernatural to you. But these are not fuzzy, half-baked notions cooked up in a late night dorm room. These are robust metaphysical frameworks rigorously tested in both the consciousness of ancient yogis and the minds of respected philosophers. It is a metaphysics that has been around for millennia. And it does a better job of explaining everything from these questions about consciousness to the weirdness of quantum physics, far more simply and elegantly than physicalism does.

Not only that but I find this metaphysics more believable or resonant because of personal experiences I have had with sacred plants ceremonies and advanced yoga and meditation. I have had the direct experience of unity consciousness. Along with the elegance of its metaphysics, those experiences confirm for me the validity of idealism.

Challenges for AI Consciousness

You can see why this presents challenges for AI consciousness. So far, universal consciousness seems to enjoy separating itself exclusively into various forms of life. In contrast with machines that we have built so far, life is self-regulating, self-perpetuating, and self-directing. It is emergent and self-organizing. Living things do not require maintenance or intervention from outside to thrive and propagate, except in the case of injury or illness.

The question then becomes, can we create a machine that will somehow capture this mysterious spark of consciousness? Is there some trick to it? Bernardo Kastrup thinks that we would need to essentially recreate life in all its wondrous complexity in order to create artificial consciousness.

Life so far has created new forms of itself through the gradual process of biological evolution. If humans were to do it with intelligent machines, it would be more of an accelerated, non-contiguous leap forward. Maybe that is possible. But viewing it in these terms makes it seems much more difficult. It suggests that creating consciousness requires more than simply scaling up the complexity of mathematical algorithms running on silicon (with large language models).

Furthermore, it is not at all clear that reality or consciousness is fundamentally computational. That could just be our own fairly recent tendency to see the world as mathematical, because of our love affair with the machine metaphor and all the marvelous technologies it has given us.

Panpsychism, Briefly

By the way, there is a similar metaphysics called panpsychism. Panpsychism suggests that consciousness permeates all of reality but there remains a material or physical world where consciousness is just one property of it. Panpsychism has what I consider a fatal flaw called the "combination problem." Maybe I'll talk about that another time.

Conclusion

We humans have never created consciousness, nor have we ever seen something non-biological have consciousness. Consciousness is still a great mystery, possibly the greatest.

We think AI systems can become conscious because physicalism and technoscience tells us that nature, life and even consciousness are machine-like, computable. With that line of thinking, if nature and life are mechanistic, then creating a new form of sentient life is simply a question of computation, or "compute" as the AI companies like to say.

But, given our current science and metaphysics, that is not clear at all.

Not only that but I think science has been able to mostly ignore metaphysics and philosophy for the past century, not to mention the discoveries of quantum physics, because it has been so effective at giving us new dazzling technologies and some semblance of technological progress.

We need to be discerning and rigorous when analyzing these questions. Because, as I explained in my last essay, a determination of consciousness can have enormous implications across all facets of society.

A failure to do so leaves these questions and conversations in the hands of the transhumanists and rationalists who are fundamentally materialists despite all of their talk of spiritual machines (Ray Kurzweil) and spreading the light of consciousness to the stars and beyond (Elon Musk).

That's why this is such an exciting time! The entire technoscientific project has reached its limits within its tacit metaphysical confines.

Science says we can only know things through the application of our rational intellect. But if we engage our embodied empathy and really connect with another being, we can experientially confirm the presence of another consciousness. In other words, maybe we are simply overthinking it.