From Epstein to Elon: The Mechanistic Malignancy at the Heart of Modernity

What to do about the hyperrational, cannibalistic worldview that permeates technology innovation, finance, and politics

I was going to publish a post about AI, creativity, and where human imagination comes from. But as an American and a human being facing the rise of fascism in the United States, and the dawning realization of the enormity of the revelations of the Epstein Files, I have to talk about that. We all need to be more vocal about this if anything is going to change.

Having said that, what I have to say today does fit squarely within the scope of my Substack. After all, I was inspired to create this Substack in the first place because of the bizarre, techno-utopian, transhumanist ideologies driving AI innovation in Silicon Valley, essentially as a counter to those ideologies. As I discussed at length a few years ago, transhumanism is an ideology that seeks to make humans “more than human,” to transcend what it is to be human, including merging with machines in various ways in order to become immortal and eventually spreading “human consciousness” throughout the cosmos by somehow uploading human consciousness to the cloud and then engineering that cloud so that it permeates all matter.

Transhumanism and related ideologies like rationalism and effective altruism essentially continue the Western project of separation, objectification, disembodiment, mechanization, and exploitation. As I explain below, the general Silicon Valley ethos and Epstein’s world are an outgrowth of that project, from their eugenicist tendencies to their distaste for all things corporeal and wild.

In diagnosing what’s rotten in technology innovation today, I recently talked about what I have been calling the Apollonian mind, this modern tendency to approach the world through abstraction, analysis, certainty, utility, and othering. To the Apollonian mind, nature, life, and the cosmos are mere machines, easily reproducible synthetically.

Echoing the gnostics two millennia ago, the transhumanists view the earth and the body as distasteful, as mere resources to be plundered in a grand mission to escape to Mars,1 and eventually into some disembodied cloud where the chosen will live on as electrical pulses.

I have also explored what Native American thinkers have described as the Windigo soul sickness that seems to underly the technology innovation ecosystem, not to mention capitalism itself. More on that in a moment.

I think these two interwoven tendencies or qualities of the Western tradition explain not only the ethos in Silicon Valley and the extractive, exploitative practices of AI companies but also the horrific, cannibalistic, pedophilic sex trafficking cult that has come into clearer view as a result of the partial release of the Epstein files. Is it any wonder that Peter Thiel and Elon Musk sit squarely at the intersection of the two?

Like Jeffrey Epstein, Elon Musk wishes to seed the human race with his own DNA. Musk also views humans as mere “bootloaders“ for an advanced race of disembodied robots. He calls those he disagrees with “NPCs,” or non-player characters. Peter Thiel, a “great friend” of Epstein, and creator of the mass citizen surveillance company Palantir, isn’t sure humanity should survive. Thiel appears at least 2,273 times in the Epstein files. It also seems that Google co-founder Sergey Brin hung around with Epstein on his island.

In other words, it is no coincidence that so many AI leaders are transhumanists, and that some of them have been in the orbit of the cannibalistic pedophile cult for so long.

The Hungry Ghost of the Windigo

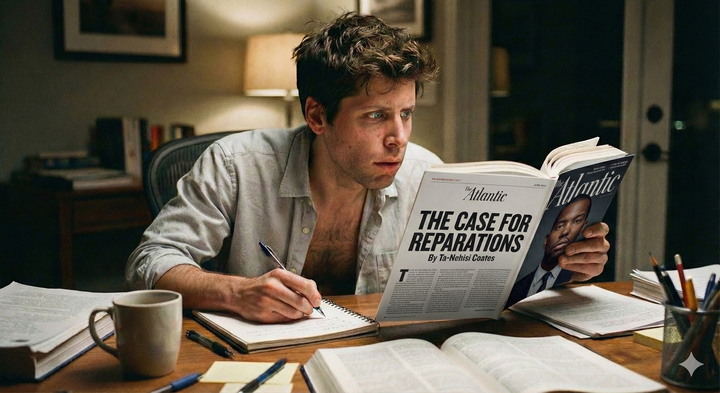

Although Karen Hao chronicled the ways in which tech companies are extractive and exploitative so thoroughly in her book Empire of AI, a few months ago I examined the reasons that AI innovation is so overconfident, extractive, and exploitative because I wanted to understand the underlying historical, psychological, and philosophical reasons for it. In that post, I borrowed a metaphor used by Native American scholars like Jack D. Forbes and Robin Wall Kimmerer: The Wétigo or Windigo. The Windigo is an emaciated, cannibalistic, insatiable ghoul from the Algonquian-speaking First Nations people of North America that wanders the frigid winter forest devouring human flesh, especially the most vulnerable.

Sounds familiar, right?

Native Americans have long viewed European colonialists as being possessed by this Windigo spirit. And, as we have seen with the horrifying revelations contained in the Epstein files, this ghoulish Windigo spirit has been haunting Western culture for centuries, reaching a state of perfection in the United States.

I am not the first person to draw a connection between the violent invasion of foreign lands and extraction of land, the subsequent extraction of time and energy from the working class, and a perverted desire to consume the life force and purity of vulnerable young girls. There is an entire body of twentieth-century scholarship from ecofeminism, Marxist feminism, and decolonial theory exploring these connections.2 In the 19th century, Karl Marx compared capitalists to vampires.3 Around the same time, while examining satanism and witchcraft, French historian Jules Michelet wrote about the perverted desire of lords and priests to consume the life force of young girls.4

The Windigo is an emaciated, cannibalistic, insatiable ghoul from the Algonquian-speaking First Nations people of North America that wanders the frigid winter forest devouring human flesh, especially the most vulnerable.

This exploitative and extractive tendency is a disturbing fact of modern existence, one that some of us are just waking up to the enormity of.

Hubris Syndrome and Elite Narcissism

When a man becomes powerful or absurdly rich, he often contracts what Lord David Owen and Jonathan Davidson called “hubris syndrome,” a supercharged kind of narcissism that includes the dehumanization of others and a “god complex” where they see themselves as more evolved, because of “superior genes.” It goes without saying that succeeding to that degree in our neoliberal, capitalist system requires some degree of sociopathy. That’s just how the system is designed.

This is why Elon Musk views most people as “non-player characters” or “NPCs.” Emotionally stunted billionaires don’t see other humans, or life in general, as real, or worthy of care or consideration. That is what the Windigo sickness coupled with the Apollonian mind does. It turns people into monsters.

Ever since the Greeks saw “barbarians” as inferior, and the Romans and then Christians perfected this attitude, the world has been subjected to this kind of violent arrogance.

Also, equating financial success with superiority reminds me of engineer’s disease, the belief that expertise in one field (usually STEM) makes one an expert on everything else. On the contrary, success within the system does not mean a person is intelligent or superior; it just means they are adept at operating the gears of a heartless machine. Engineer’s disease is how we end up with AI engineers thinking they know the first thing about human intelligence or consciousness.

In short, when you see nature as separate, you colonize. The new world, Mars, bodies, the collective psyche. Except our collective psyche cannot be colonized without our consent. That’s where the work is.

Decadence and Aristocratic Malignancy

All of this is nothing new. It tends to come to a head in times of decadence. Think Caligula or Nero in ancient Rome, or the pre-revolutionary French aristocracy and the Marquis de Sade. Citing Rich Cohen in the Paris Review, recently made this point on her Politics Girls podcast, in an inspiring and educational conversation with Joanna Johnson:

The most powerful people in the moment of decadence—ancient Rome, dynastic China, Vienna between the wars—were once dominant societies at the end of an age. As power wanes and imperial dreams fade, the lust for conquest turns inward, and it manifests according to lavish conspiracy theories in the velvet rooms of secret societies, where this taste for arcane ritual and human sacrifice is rooted in a maddeningly arrogant belief: “There is nothing I want that I can’t have, and there is nothing I can do that I can’t get away with.” [T]his has been happening for generations, like every single time. It’s a... it’s a cycle. And this is where we end up. It’s interesting because I guess [Cohen] alludes to the fact that it’s at the end of a society, but I think it exists all the way through.

In other words, this malignancy that Cohen says appears during a society’s decline into decadence permeates the machinery throughout but only becomes visible in its full grotesquery in those final stages, as we are seeing now.

In light of all this—the rise of fascism, and the questioning of the very fabric of modern society, not to mention the destabilization introduced by AI automation and the degradation of the information ecosystem—what the hell can we do? How should we be thinking about this?

Balanced Ways of Knowing and Being

Although the Apollonian mind and the Windigo sickness are intertwined to a large extent in the way they objectify, divide, and other, a good place to start addressing this societal undercurrent is to cultivate what we might call right-hemisphere qualities: seeing connections and wholeness; cultivating our intuition, emotional intelligence, empathy, and embodied intelligence; and moving as relational selves that are interconnected with others, with nature, and with the cosmos. In other words, practicing traditional indigenous ways of being of kinship and reciprocity.

We can’t think our way out of this, at least not in the old ways. Instead of trying to solve the problem or prop up untenable institutions, maybe we should accept that the way of life we have known for our whole lives is dying.

Hospicing Modernity

Obviously what we’ve seen in the Epstein files coupled with the rise of fascism is a wake up call. We don’t need political reform or to revamp our institutions. We need a complete, top-to-bottom rethinking—no—re-feeling, re-relating of our entire worldview. The Democrats can’t save us. Technology can’t save us. AI can’t save us. Only we can save us. We the people. And that means all the people, and especially the global south.

Disembodied thinking that alienates from nature is what got us here. Moving towards wholeness is the way forward.

A good place to start addressing this societal undercurrent is to cultivate what we might call right-hemisphere qualities: seeing connections and wholeness; cultivating our intuition, emotional intelligence, empathy, and embodied intelligence; and moving as relational selves that are interconnected with others, with nature, and with the cosmos.

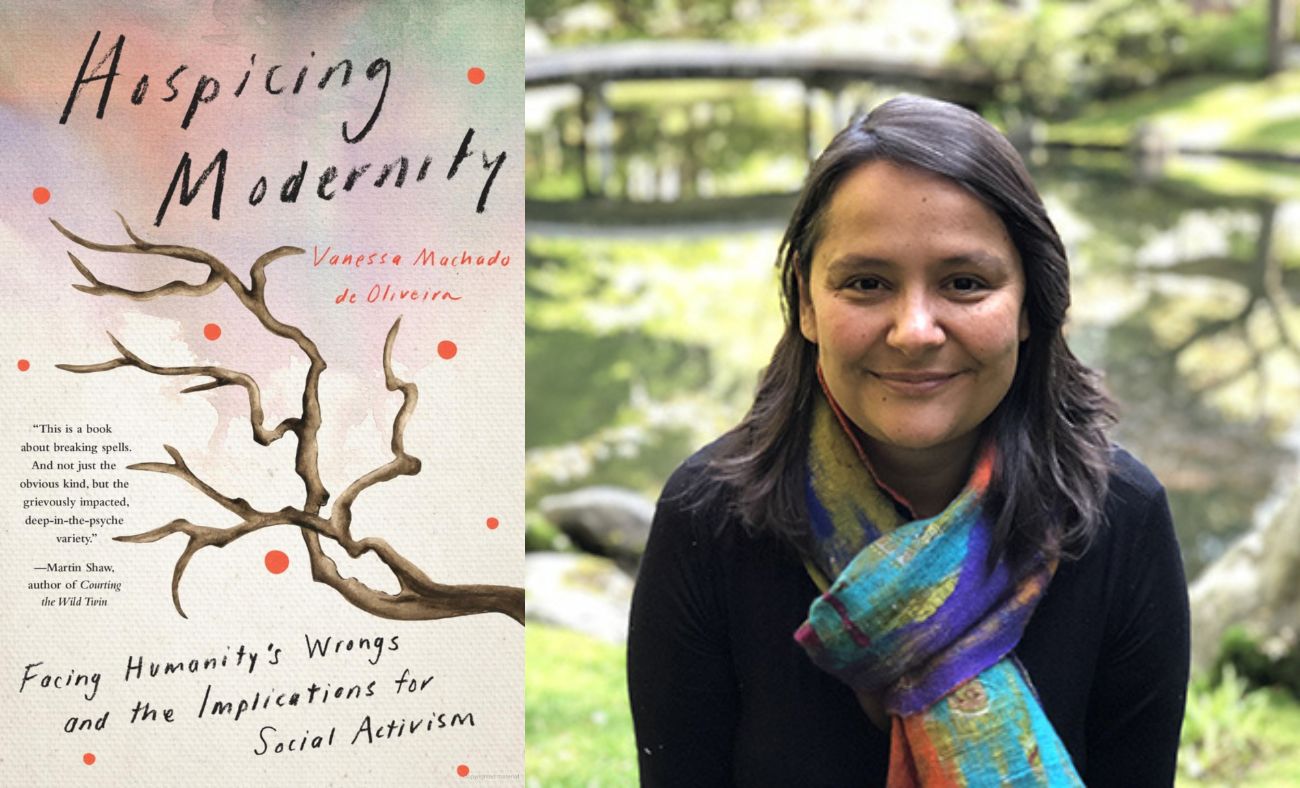

To that end, inspired by activist and scholar Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, we need to accept that modernity is dying and take steps to hospice that expiration. What she means by modernity is this dehumanizing ethos of extraction, exploitation, separation, and endless growth.

According to de Oliveira, while modernity dies, something else is being born. We cannot know yet what that something is, but we can act as midwives to these emerging possibilities by clearing space and remaining present in the uncertainty. Part of that process is letting ourselves feel the feelings it brings up, while maintaining the integrity of our nervous systems. Along those lines, the late environmental activist Joanna Macy talked about the necessity of “honoring our pain for the world” as a necessary part of the spiral of the work that reconnects.

From this perspective, authoritarianism and a lack of accountability by billionaire pedophile cannibals are the death rattle of modernity. It is a bad, ugly death, one only befitting of a bad, ugly history.

The Six Cs

de Oliveira identifies six “ego-logical” addictions that keep us wedded to modernity: comfort, control, convenience, certainty, consumption, and coherence (needing a consistent narrative to paper over the messy contradictions). Embracing the palliative mindset toward modernity will be uncomfortable, inconvenient, and uncertain. It will require a release of the need for control, and a reexamination of our relationship to consumption and accumulation. And it will require us to let go of old stories about how to live as citizens of this earth, and to listen for new stories.

Worlding the World

de Oliveira also talks about how modernity “words the world,” reducing everything to abstract concepts. I alluded to this in my last post about how language is not synonymous with intelligence and how this undercuts the viability of the current approaches to AI to achieve anything resembling human intelligence. Instead, de Oliveira recommends “worlding the world,” a shift from treating the world as a noun (a collection of static objects to be used) to treating it as a verb (a continuous, relational process of becoming). It is an invitation to move away from the “One-World” perspective of modernity—which claims there is only one objective reality—and toward a pluriverse, where multiple worlds and ways of being coexist and “world” together. I would like to explore this more deeply in a future post.

Developing Emotional Stamina and Radical Tenderness

It goes without saying that all of this will require emotional stamina. It is absolutely essential that we learn how to regulate our nervous systems. For me, that includes practicing yoga, meditating, breathing, and cultivating a deep connection with nature. But not in a bypassing, checked-out way. We do all of this so that we can midwife the death of modernity, not turn away from the intensity but facing it in a resourced way. We are going to need spiritual warriors during this time of upheaval.

de Oliveira recommends radical tenderness, a fierce, grounded capacity to stay soft and open in the face of immense suffering and systemic collapse. Radical tenderness is the willingness to acknowledge that we are all “messes.” We are flawed, hypocritical, and deeply wounded by the very systems we are trying to change. So, instead of judging ourselves or others for our fears or attachments to comfort, we host them with tenderness. We say, “I see you are terrified of losing your status; I hold that fear with gentleness, even as I refuse to let it lead.”

Conclusion

I am not saying that all AI evangelists and technology leaders are morally bankrupt or part of the Epstein class. I am simply pointing out that the roots of the Epstein phenomenon and the attitude of AI companies flow from the same toxic sources. Therefore, any kind of serious reform needs to include a reconsideration of the Apollonian, Windigo worldview.

Understanding the Windigo sickness and the Apollonian mind virus isn’t just an academic exercise—it is essential to reimagining what we build and why. Until we reckon with the extractive, disembodied worldview that drives both the Epstein phenomenon and the AI industry, we will keep building technologies that reflect the same sickness, no matter how many safety guardrails we add.

Reconsidering the Apollonian worldview and expunging the Windigo sickness from our society is some deep inner and collective work. In order to contribute effectively, it is crucial to stay focused on the positives—that there is widespread, increasing awareness of the problem, and the fact that something new is being born.

Let’s keep talking about it.

Musk recently scaled back his ambitious Mars mission to building a “self-growing city” on the moon. ↩

Some good starting points include: Caliban and the Witch (2004), by Silvia Federici; Patriarchy and Accumulation (2022) by Maria Mies; Staying Alive (2016) by Vandana Shiva; and The Wretched of the Earth (2021) by Frantz Fanon. ↩

See, e.g., Capital, Volume I (1867). ↩

La Sorcière (1862), titled Satanism and Witchcraft in its English translations. ↩