AI Empires and the Soul Sickness of Silicon Valley

Creating AI for the people by moving from empire technologies to humane technology innovation and conscious stewardship

In my ongoing exploration of what’s rotten in Silicon Valley tech innovation and the ideologies driving it, last time I talked about the pandemic of what I called the Apollonian Mind Virus, a tendency throughout the modern world to favor cold, disembodied hyperrationality and cognitive intelligence over all other ways of knowing and being—over intuition, emotional intelligence, embodiment, and wisdom. This Apollonian orientation toward nature has ushered in what Sam Altman has dubbed the Intelligence Age. In short, “Apollonian” describes the worldview and theories of intelligence behind current approaches to AI.

Today, I explore an adjacent pandemic of the mind or sickness of spirit that is insatiable, extractive, and exploitative: The hungry ghost of the Windigo. I argue that current approaches to AI are largely the result of these two features of the modern, Western ethos—the interwoven helix of the Apollonian Mind and the Windigo soul sickness. I then close this post by beginning to explore whether there is a better way to innovate and evolve, collectively.

As a reminder for those who are new here, I am examining the Silicon Valley ideologies that are driving artificial intelligence innovation today because I think there is a better way to build an engine for creating a more human future. I agree with CEO and founder of Anthropic Dario Amodei that AI should be “a force for human progress.” I just think the word “human” should represent all of humanity alive today.

To be explicit, the questions I am attempting to answer on this Substack, my YouTube channel, and my podcast are as follows:

- In light of the fact that technology innovation is the perfection of our Apollonian worldview and a voracious, extractive, colonialist force that I (and others) call the Windigo (more below), can we find a way to make technologies (like AI) that serve humanity rather than forcing humanity to be more machine-like?

- Is an evolutionary, liberatory, and humane interplay between conscious technologies (like kriya and meditation) and material technologies (AI and the internet) possible?

- How can we become more fully human alongside technological innovation, instead of outsourcing our evolution to machines?

All of these questions arose within me in a single moment during a “conscious AI” retreat I attended in Northern California in April this year, when I realized in horror that a majority of the attendees were perfectly willing to outsource their evolution to machines, to see humans as mere algorithms, and to follow the current extractive approach to AI innovation wherever it leads. If self-styled Buddhists and conscious technologists with good intentions are afflicted with the Windigo sickness I describe below, what can be done?

This post is another step toward answering the many questions that arose at that retreat, and is primarily focused on the first one—addressing the Windigo mindset that drives technology innovation today.

The Windigo

As an American man of European descent I am intensely curious about why, alongside the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, the nation-state, civil and common law, and capitalism, the lasting legacy of Europe is colonialism. Or maybe alongside is the wrong word. Maybe those are all various strands of a unified force or ethos. After all, they are all instruments of distancing the human from nature and exerting absolute control over the natural world, of exerting what Joanna Macy called “power over.”

Native American writers like Jack D. Forbes and Robin Wall Kimmerer called this extractive, consumptive force behind colonialism the Wétigo or Windigo, after an Algonquian myth about a voracious, insatiable ghoul who wanders the world devouring everything and everyone it encounters. For these Native American thinkers and activists, this Windigo force is an epidemic of the mind or spiritual sickness characterized by insatiable greed, aggression, domination, and objectification. Author Paul Levy has also written about the Windigo as a “mind virus” and a pandemic.

A voracious, insatiable, extractive force also accurately describes the ethos behind Artificial intelligence innovation. Where AI itself is an echo of the Apollonian Mind—and an unpredictable, schizophrenic savant—the arrogant, bellicose ethos behind it is the Windigo, a hungry ghost of unbounded extraction and consumption for its own sake.

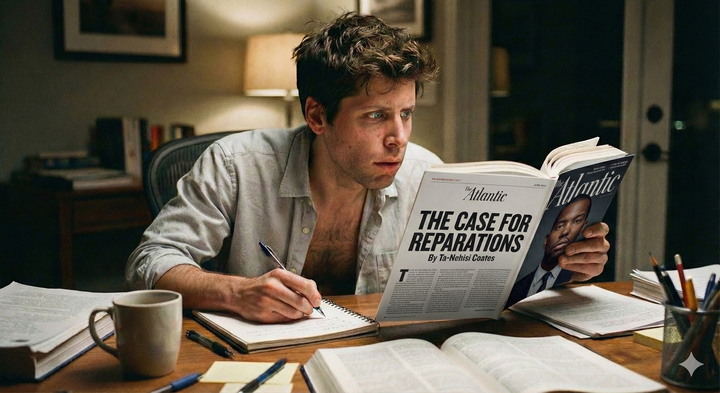

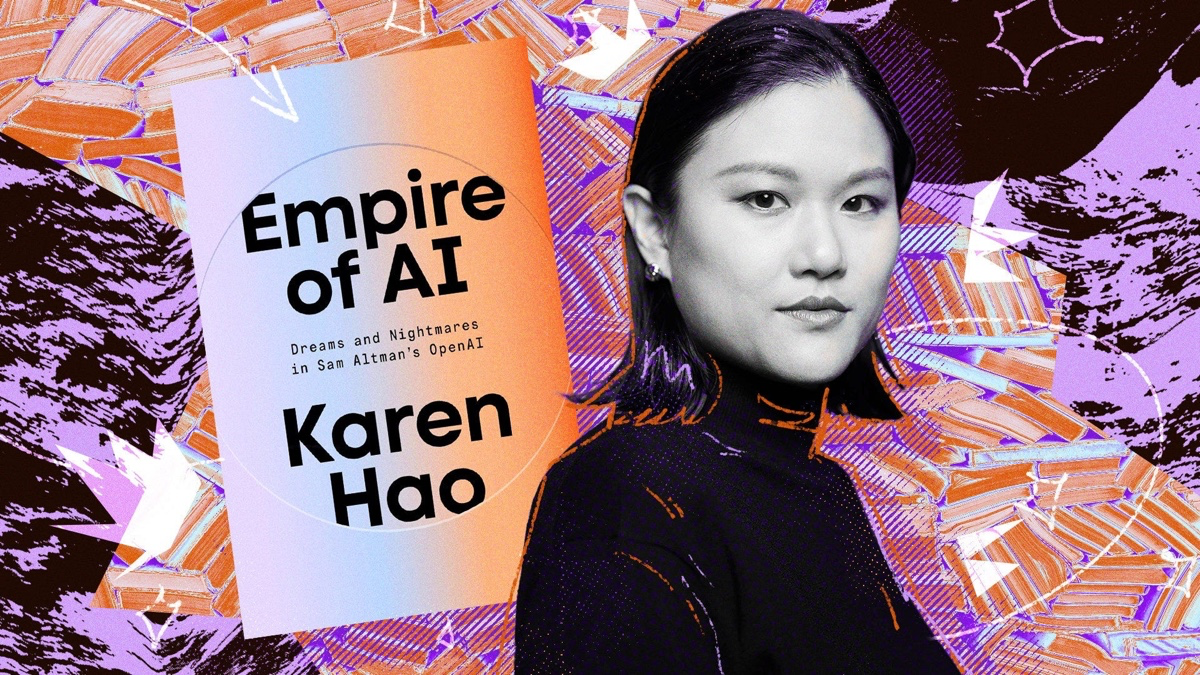

Empire of AI

In her recent book Empire of AI, Karen Hao argues that major AI companies operate much like the imperialist empires of the Age of Discovery by engaging in digital colonialism—extraction of resources, exploitation of labor, and the concentration of power and wealth under a unifying, self-justifying ideology. Without calling it the Windigo, in her book she thoroughly documents the symptoms of this sickness among AI companies.

In terms of extraction, Hao shows in her book that large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude require enormous physical resources in the form of energy and clean water, to the detriment of local ecosystems and communities. And this urgent, voracious consumption of resources by multiple companies is justified by what is primarily an unfounded promise of future benefit. After all, LLMs are not likely to lead to AGI or superintelligence, and have so far offered minimal benefits, especially in proportion to the resources required. As I said a year ago, AGI is really hard.

Not only that but these AI systems are trained on the creative work of millions of humans in an extractive way, ignoring intellectual property rights. And the unrealized promise of superintelligence and some future robot utopia has fed a self-fueling investing frenzy where AI companies are round-tripping over $1 trillion dollars.

Furthermore, as Hao illustrates in her book, AI models are primarily trained on the hidden, cheap, and traumatizing labor of labelers and content moderators in the Global South. Workers in places like Kenya, Venezuela, India, and the Philippines are treated as undervalued and expendable by the AI companies.

All of these externalities are hidden behind a smoke screen of utopian visions and economic necessity, where the “good guys” of Silicon Valley must defeat China in a zero-sum game.

The Origins of the Windigo Soul Sickness

Inspired by the work of Forbes and Kimmerer, I have come to see the Silicon Valley innovation ethos as deeply Windigo. In other words, technology innovation today is driven in large part by a kind of mental and spiritual illness. What else would explain the release of an app like OpenAI’s Sora 2? Or Marc Andreessen’s Techno-Optimist Manifesto? Or Peter Thiel’s rants about the arrival of the Antichrist, and not wanting humanity to survive?

It is no accident that Peter Thiel is describing opposition to the Windigo as the Antichrist. These are archetypal forces that have been at odds since the dawn of civilization. To the Windigo mind, slowing down to regulate technology or consider the needs of the earth and all the people on it stands in opposition to Thiel’s mechanistic, messianic mission.

Other billionaires like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg are also infected with this Windigo sickness. Why else would billions of dollars not be enough to satisfy them? Why else would they envision a mechanical future where humans exist only as simulations in the cloud? And why would they behave like sociopaths, completely lacking in humility and empathy?

Whereas the hyper-rational Apollonian Mind is a legitimate way of approaching the world so long as it is balanced by the creative, intuitive Dionysian, the Windigo tendency is nothing more than a sickness; there is nothing redeeming about the Windigo mentality.

Whence the Windigo?

As Robin Wall Kimmerer reminds us, this Windigo tendency lives within each of us. But, gazing back over human history, it seems to have metastasized primarily in Europe, and then in the European colonies. Where did this European Windigo come from? Why was Europe so industrious, belligerent, and colonialist for over three centuries?

Scholars think it was a combination of ecological precarity in parts of Europe (deforestation and cycles of plentiful harvests followed by droughts), the othering of so-called “barbarians” by the Greeks and Romans partly in response to the Greco-Persian war, and the ways that wheat farming led to rapidly growing populations who developed standing armies with access to bronze and, eventually, iron weaponry. In other words, the root causes were environmental, cultural, political, philosophical, and technological.

Because these factors are interrelated it is difficult to point to one initial spark or “original sin.” For example, deforestation led to soil erosion, which created endless cycles of scarcity and starvation, which justified seeking more natural resources beyond one’s borders. But this deforestation was the result of the need for raw materials for shipbuilding and metallurgy (fuel for smelting). So it was a vicious cycle.

If I had to point to one cause for the this sickness, I think it is this idea of “civilization” versus “wild” nature, and “savage” others. Although Jack D. Forbes points out that the Windigo originated with the Egyptians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Persians, it was the post-Socratic Greeks in particular who perfected this othering, being, as they were, obsessed with reason, order, law, and control. The Greek city and the cultivated field were reflections of an Apollonian orientation. In contrast, the “wild” forest represented to the ancient Greeks the dark, threatening other, containing chaotic natural and supernatural dangers like wolves, bandits, barbarians, monsters, and the Dionysian satyrs and maenads indulging in debaucherous, ecstatic rituals. Oh my!

Civilization vs. Barbarism

Speaking of barbarians, the Greek word bárbaros (βάρβαρος) was originally a neutral term used to describe anyone who didn’t speak Greek (as foreign speech sounded like “bar bar bar” to the ancient Greeks). So barbarians were initially simply non-Greeks. But this changed dramatically in the 5th century BCE with the Greco-Persian Wars. Suddenly, the Greek identity became that of a sophisticated, liberated people living in a simple, austere democracy in contrast with the supposedly decadent yet savage tyranny of the Persian Empire.

As the Romans took over as the dominant European empire, they borrowed this concept as an instrument of imperial propaganda, justifying the violent conquest of the “savage and lawless” Gauls, Celts, Iberians, and German tribes. The Romans saw it as their duty to bring peace, order, and civilization (Pax Romana) to the rest of the world. In ancient Europe, savagely installing “peace” outside one’s territory was seen as a form of “civilization.”

Now we begin to understand Mark Zuckerberg’s and Elon Musk’s fascination with ancient Rome and the larger “RomeBro“ phenomenon.

And thus began the longstanding practice of othering and projection, where every accusation is a confession, an unconscious habit perfected by MAGA today. For those afflicted with the Windigo sickness, violent consumption of land and exploitation of labor is “civilization” and “progress,” whereas the reciprocal, sustainable lifestyles of indigenous people is pathologized as “barbaric,” “savage,” and “primitive.” The “savages” are accused of practicing human sacrifice, while the “civilized” slaughter untold millions of indigenous across the globe in the name of “civilized” European nations. Jack D. Forbes pointed out the hypocrisy in this attitude, saying, “few, if any, societies on the face of the earth have ever been as avaricious, cruel, violent, and aggressive as have certain European populations.”

The Rise of the State and Standing Armies

The next development in the creation of the European Windigo is the appearance of standing armies. Although the agricultural revolution in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East with its wheat and barley surpluses made the centralized state possible, it was the increasing presence of standing armies that evolved into a self-fulfilling prophecy of continuous conflict. Before that, wars were fought with a citizen militia that farmed most of the year. With a full-time army, there arose a powerful warrior class with a vested interest in justifying its existence through endless conflict and territorial expansion. Add to that the development of bronze and then iron metallurgy, which gave these societies a decisive military advantage over the “barbarians.”

Environmental Factors

The rise of the Windigo was also an accident of geography. Because of its steep, rocky landscape and intensely hot and dry summers, the Mediterranean basin is especially vulnerable to deforestation. Once the trees covering a hillside are felled, the sun bakes the soil into a hard crust. Then, the winter rains hammer this crust, rushing over the surface instead of being absorbed.

Plowing and overgrazing made this worse. In a way, it was a vicious cycle that the spreading European civilization never recovered from. Because of the relentless pressures of a growing population and the need for fuel and building materials, deforestation only accelerated across Europe in the Middle Ages. By 1086 only 15% of England was wooded. On the eve of the Black Death a few centuries later, that figure had plummeted to 6%. By the 14th century, only 10 percent of Europe’s land area was forested. This then led England and other parts of Europe to switch to coal as as source of fuel, which then led to worsening air pollution.

In short, alongside its trademark arrogance, the European psyche became one of resource scarcity, zero-sum logic, and therefore of conquest. By the Age of Discovery, the mindset and machinery of imperialism also had a powerful moral and legal justification.

Christian Fuel for the Colonial Fires

In the 15th century, at the start of the Age of Discovery, two successive Popes in Rome issued a series of papal bulls (decrees) that gave Christian nations a theological and legal right to conquer the “savages,” who now had no rights to land or sovereignty. It became the “white man’s burden” to “civilize” the “heathen” peoples of the world, “saving” their souls and giving them “culture.”

You might say that Christianity by then was the operating system of colonialism, about as far from the humble, love-your-neighbor message of Jesus’ teachings as a religion can get.

The Antichrist of Stagnation

Now Peter Thiel’s framing of anything opposed to this Windigo tendency as the “Antichrist” comes into clearer focus. Thiel’s Antichrist is not a horned figure with hooves and a spiky tail but degrowth, regulation, and Greta Thunberg precisely because those ideas are antithetical to the crazed Windigo mind.

Again, I am not saying that this sickness is inherent to being of European descent or within the European tradition. It is a spiritual sickness that can infect anyone, although Silicon Valley today has elevated it to an art form in the way that it approaches technology innovation. It’s more than a desire to invade other countries either overtly or covertly; it’s a way of thinking, a way of life that thinks hyper-rationally of voracious expansion for its own sake, and looks to malignant growth as the solution to every problem. That is why Latin American and Indian scholars talk about the need to decolonialize hearts and minds, to cure the infected, which is all of us moderns now.

As we can see, the lasting legacy of European civilization is not Christianity or secular rationalism but the idea of endless, urgent growth and expansion at all costs. It’s a means-justifies-the-ends ideology. Of course, it goes without saying America took up the Windigo mantle from Europe after World War II, if not after the Spanish-American War in 1898.

The Apollonian Windigo

Although the Windigo fuel for centuries was Christian ideologies of superiority and future salvation, with the arrival of the Apollonian mind during the European Enlightenment, it found a more pure form of ideological fuel: Human reason, science, and technology replaced God as the agent of salvation, leading humanity toward a technoscientific utopia. Instead of the Second Coming, we now have the Singularity, where our digital soul will not ascend to heaven but to the cloud.

It is these two intertwined mindsets or worldviews that have dominated modern civilization and become the twin strands of the current approach to artificial intelligence.

The question I am asking and want to keep attempting to answer as I write these posts is whether, given the forces behind AI today, it can be transformed or alchemized into a force for the benefit of the larger human and non-human world. Can AI be created or repurposed to subvert the very Apollonian and Windigo ethos it arose out of?

For those of us concerned with the current direction of AI innovation, what can be done?

Indigenous Worldviews

As a countervailing force against the Windigo, the Native American scholars I cited above recommend a return to indigenous principles and an indigenous worldview, one not dissimilar to the philosophically idealist Yog-Vedanta worldview that my long-time readers will be familiar with.

Briefly, the Native American worldview (and that of many other indigenous traditions) is one of kinship and relationality, the idea that all of nature is part of a vast family of interconnected subjects, and that includes animals, plants, rivers, and mountains. Within that view, the cosmos is a web of relationships. Therefore, all of one’s relationships are governed by a sacred reciprocity, where one doesn’t simply take from nature or from another without giving back.

Both the Native American and Yog-Vedanta worldviews are fundamentally non-dual, in opposition to the materialist subject/object dualism of scientism. And they both see the cosmos as fundamentally conscious, as the Anima Mundi or World Soul. For the ancient yogis, the cosmos is Shakti or Brahma, a “divine play” and creative dance. For the Native American tribes, the Earth is a living, conscious mother. Even their core ethics of reciprocity and karma are similar, in that they underscore the fact that, because we are interconnected with all other subjects in the cosmos, any action we take affects the whole. Granted, the immanent Native American goal to live in harmony within the natural world may seem to differ from the some interpretations or manifestations of the Yog-Vedanta goal of liberation from the cycles of birth and death. But the yogic traditions I follow are also immanent, recognizing that there is nowhere else to be but in the manifest cosmos.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, in particular, references an Anishinaabe prophecy of the Eight Fires. According to this prophecy, humanity is currently in the Seventh Fire, where the fire keepers retrace their steps in order to gather up the fragments of songs, stories, and sacred teachings so that the Eighth Fire can be kindled in a great coming together of peoples around the world to walk a “soft path of wisdom, respect, and reciprocity.” Kimmerer characterizes this as a synthesis of indigenous wisdom from around the world—indigenous European knowledge, indigenous Asian knowledge, and indigenous knowledge from the Americas. Despite the immense diversity of those traditions, for our purposes, we can boil down their varied manifestations into a synthesis that reflects the Native American and East Indian worldviews summarized above.

But what does this look like in practical, concrete terms, especially in the context of technology innovation?

A Way Forward

Now that we’ve recognized the general shape of the challenge, what can be done? The hurried, myopic, gambler mentality behind the way AI is currently developed (e.g., Sam Altman wanting to throw $7 trillion dollars at LLMs in the hopes that scaling will lead to an ill-defined machine messiah) is just how business is done. This approach to AI is a “blitzscaling” model that accepts ethical and social breakage as the cost of doing business.

Who in their right mind would deviate from that tried and true path to the American Dream of a frontier utopia? It feels a little like I’m proposing a revolution of some kind. Or being a total buzzkill, although there is a growing consensus that we have hit the “Too Big To Fail“ era of the AI bubble. And Michael Burry of Big Short fame has bet $1 billion on the AI bubble bursting.

In any case, I think it is time for bold proposals. In the same way that the explosion of LLMs is forcing us to confront philosophical and spiritual questions about what it means to be human and the nature of consciousness, I think it’s forcing us to reevaluate other assumptions, like what makes for a good business model. Because, as I am arguing in this post and this series, AI is the apotheosis of the Scientific Revolution and its ideologies, it seems to be the tipping point into what Thomas Kuhn called a paradigm shift that underpins scientific revolutions. Except this time it’s the beginning of a revolution in worldviews, socioeconomic and sociopolitical theory, and approaches to business. As Kimmerer suggested, we must walk back over where we have been in order to gather up only what is relevant for what’s next—fragments of wisdom and sacred knowledge in order to shape the new paradigm.

Paul Levy suggests that the antidote to the Windigo virus is simply exposing it to the light, a sort of collective shadow work. Robin Wall Kimmerer proposes that we shift our worldview and move to a gift economy. Jack D. Forbes suggested something similar.

Going back to the questions that I began with, can we find a way to make artificial intelligence that serves humanity rather than creating a supposed machine god and forcing humanity to be more machine-like?

Although these are big questions without easy answers, I think we can address the challenges presented by the double helix of Apollonian thinking and Windigo sickness in three parts, each of which draws on a different part of my background as technology philosopher, attorney, and software engineer:

Raising Awareness

The first step is talking openly and honestly about the current state of affairs. That was the impetus behind this post. It’s crucial that we raise awareness of the harms of the Windigo tendency and cultivate technology leaders who are devoid of the Windigo sickness, leaders who understand that every participant in the human and non-human world is interconnected, leaders who prioritize reciprocity.

Because technology reflects the consciousness of those creating it, I think finding or cultivating leaders and innovators with their heart in the right place is paramount. In the same way that toxic startup founders create a toxic workplace culture that can never be fully remedied, sociopathic innovation leadership will lead us into a sociopathic future full of toxic, extractive technologies. Letting Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and Sam Altman set the innovation agenda will only worsen the problems highlighted above.

A More Humane, Innovative Approach To How We Do Business

Now that OpenAI has completed its for-profit transformation, I think it’s time to look in the other direction, not just at the non-profit model, but to corporate structures for AI companies and organizations that fundamentally change the incentives, such as a public benefit corporation (PBC) or even steward ownership.

Steward ownership is a purpose-driven business structure that prioritizes a company’s long-term purpose and well-being over maximizing short-term profits for external shareholders. It does this by separating voting rights (control of the company) from economic rights (profit) to ensure the company is guided by its mission and those actively involved in its operation. In other words, a steward-owned company is “owned” by its purpose. There are no shareholders exerting undue pressure on short-term gains.

The voting rights remain with those personnel who are actively managing the company and connected to its operations and purpose. Those rights cannot be sold or inherited, and they don’t generate any financial returns. Instead, they stay with the company over its lifetime as personnel change. Any profits generated by the business, and all assets, are held in support of the company’s mission, so they are reinvested in the business to cover capital costs or distributed to employees.

Had OpenAI begun as steward-owned it would have been forced to stick to its original mission to ensure that “AGI” benefits all of humanity. Instead, we get Sora 2 and pleas from its CFO to have the U.S. government guarantee its insanely risky investments.

Although steward-ownership is a corporate structure that has been around for over a century going back to Zeiss-Stiftung in Germany, it is relatively rare. One US-based example is the outdoor clothing Patagonia, who transitioned to steward ownership in 2022. They leveraged existing U.S. trust and corporate laws, creating two entities: The Patagonia Purpose Trust (the steward) and the Holdfast Collective, a non-profit that manages the profits and reinvests them back into the business, primarily to address the environmental crisis.

No doubt incorporating as steward-owned is challenging. Not only is the corporate structure complex from a legal standpoint but raising capital requires finding niche, mission-driven investors who understand that there can never be an “exit” or massive returns on investment, let alone a say in how the company operates.

Still, imagine the first AI models and AI company built with a sense of kinship and reciprocity, and structured to remain that way! I think it would resonate with a lot of people and stand as an attractive alternative to the crazed Windigo AI systems on offer today.

Building Hearth Technologies

Finally, what if we built technology itself on the ensouled principles of kinship and reciprocity, instead of voracious extraction and consumption? We could call these alternative technologies “hearth” technologies. Where empire technologies like social media or Sora 2 extract value from the periphery and concentrate it in the center, a hearth technology radiates warmth outward. Instead of atomizing individuals, a hearth technology creates and empowers communities. A hearth technology implements reciprocity by cultivating lasting relationships built on trust and a give and take instead of on monopolizing attention and fostering addiction.

Could an AI model or system be built this way? There are already a few indigenous AI systems trained ethically on indigenous data, including a Māori Speech Model and a collaboration in Australia between Indigenous Traditional Owners, Australia’s national science agency, and Microsoft to manage Kakadu National Park. What about a general-purpose hearth AI? Perhaps we can draw inspiration from the new EU models Apertus and Aleph Alpha that were ethically trained and are EU-AI-Act compliant.

In any case, taking negative inspiration from the way that Elon Musk is intent on creating an anti-woke AI in Grok, I think we need to consider creating AI models and a system that embodies an ensouled or indigenous ethos of interconnectedness, reciprocity, and community.

I have recently been talking to some friends and colleagues about creating just such an AI. And there are several inchoate attempts at a “Gaia AI” in the works across disparate groups around the world. I would also be interested in starting a think tank to explore these ideas.

More on all of that in future posts.

Until Next Time...

I started writing this post in an attempt at naming and understanding the consumptive, extractive force—this Windigo force—driving AI innovation. I had no idea it would lead to alternative corporate structures or hearth technologies.

Why does technology innovation have to run on these feast and famine cycles of exuberant hype and duplicative investment followed by enormous crashes? Why does technology innovation have to feel like gambling? I think it’s because of our Windigo tendencies.

My journey of stumbling into the myth and metaphor of the Windigo has been enlightening but has also only just begun. I know that there are already organizations out there exploring these questions from an explicitly indigenous standpoint. I offer gratitude and respect to all who have come before. My only intention here is to raise awareness and explore uplifting paths forward.

More on all of this soon....